This post is about Five Eyes, a new installation and artwork, and about ways of seeing and thinking about systems. For direct access to Hyper—Stacks, visit hyper-stacks.com.

This week sees the opening of All of This Belongs to You, an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London which explores the museum’s role as a civic and national institution. I was commissioned to create an installation for the show, and I’ve been working with the V&A and a number of its departments for over six months to realise it.

The installation is called Five Eyes, and takes its name from the alliance of English-speaking signals intelligence agencies, from Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the USA. Each agency has its own showcase in the museum’s magnificent tapestry galleries, containing a selection of objects from the collection, as well as files from the archives detailing the history and provenance of these and related objects. Each cabinet tells a short story about the history of intelligence and how it shapes the world.

For example, the UK’s retention of the British Indian Ocean Territory, its displacement of the Chagos Islanders and its leasing of Diego Garcia to the US, all in the name of maintaining a signals base in the Indian Ocean, is told through a souvenir figurine of a nineteenth century theatrical production of Paul et Virginie (a colonial fantasy of a Rousseauian state of grace in Mauritius, where many of the Chagossians were dumped after exile); a mendicant’s begging bowl carved from a coco-de-mer (the strange, once mythical fruit found floating in the oceans and originating from the Seychelles); and a pair of bracelets which belonged to the Empress of Abyssinia (site of the NSA’s previous regional base at Kagnew, and depicted in a series of watercolours in the V&A made by Commander Robert Moresby, who also made the first survey of the Chagos Archipelago on behalf of the British Admiralty in 1838. Spoils of war, they are also relics of imperial adventures in themselves).

You can explore the installation further at its own dedicated website, and there are more photos on Flickr.

The objects were initially selected from the collection by a piece of software I wrote to analyse the V&A’s digital collections database, containing the details and histories of some 1.14 million objects. In a similar operation to that which powers A Quiet Disposition, the collection was subjected to a process of sigint and surveillance, building a network of associations and implications which could then be examined, traversed, and analysed further. This system can also be explored online: called Hyper—Stacks, it underlies and extends the physical installation, allowing visitors to build their own collections and explore the unusual correlations between objects that this hybrid of curator and machine throws up. It serves to both open up the collection to new paths and discoveries, and to open its own operation to scrutiny and understanding.

In this work I wanted to explore the parallels between museums, intelligence agencies, and software programmes themselves: reduced to processes, each is an embodiment of a certain set of politics which is not always visible to the outsider, or to those subject to them – or even, as agglomerations of histories and departments, those who nominally operate them. Each is also a model of the world and a way of seeing it, but crucially it is an operational form of seeing, actively remaking the world to conform to the model it attempts to reproduce. By critically analysing and understanding these processes, it may be possible to influence the world that they are building around us. In the case of the intelligence agency, this influence may take the form of blocking or redirecting its gaze; in the case of the public institution it may consist of reconfiguring its historical narratives to better represent the experiences of the excluded; in terms of software it is a process of recognising and asserting agency within an increasingly technologically augmented and mediated culture and society. Each of these forms of action, these strategies, is one of systems literacy: understanding complexity and embodiment in one domain, and being able to generalise that understanding to other domains: legal frameworks, social codes, nation states, domestic politics, corporate hegemonies.

The Five Eyes installation is, in part, another in a long line of works which makes visible the invisible in broad terms: both literally in the rarely seen archive files which support the objects on display – their own data shadows, or metadata – and more figuratively in the exploration of provenance and politics within the museum. As always and increasingly when undertaking this work, I feel the limits of its approach most keenly, and want to use this opportunity to explore some related examples.

Following the release of Seamless Transitions, my film for the Photographer’s Gallery which used architectural CGI visualisation to explore sites of immigrant detention and deportation, several people recommending I go see John Gerrard’s work, showing in London at the same time.

Gerrard uses architectural CGI techniques as well, from a background position of photography, to explore monumental infrastructural sites. His Solar Reserve is a real-time visualisation of a solar power plant in the Nevada desert, a 24-hour rendering of an unearthly site. More pertinently, Farm, a still of which is shown above, is a model of a Google datacentre in Oklahoma, composed from 1000s of photographs taken from a helicopter when Google refused him permission to photograph on site.

There’s something very distancing about Gerrard’s technique: while impressive, it renders these contemporary monuments to power (both electrical and political) so vast and unreal as to be unapproachable. Timo Arnall’s Internet Machine (excerpt below) offers, to me, a far more visceral experience of this power, being immersive, deafening, and shot from eye level. We’re not peering over the walls of these places, we’re inside them. The internet is real. Moreover, Gerrard’s work, while making visible such sites with a great fluency of technique and clear mastery of the materials, seems to lack a literacy in its subject, opting for straight-faced reproduction, when, for me, the specific possibility of using digital tools is to show how such apparently neutral ways of seeing and constructing can activate or subvert their latent politics.

In short, there’s nothing for me operational about Gerrard’s impressive portraits: they remain a curiously classical photography, albeit one constructed incredibly carefully and with cutting-edge tools. Because, ultimately, the tools themselves are not the issue, but what we (now) know the image can do. Trevor Paglen’s shots of US intelligence agencies (the NSA, below) are traditional photography in every possible sense, and share Gerrard’s helicopter perspective, but Paglen’s images are designed to enter into the wider sphere of discussion, to affront and elbow aside the official photographs and narratives of these places. By releasing them under a free license, the photographs become part of something wider and more networked, part of a discourse, which traditional forms of representation and distribution are incapable of doing.

Julian Oliver’s project Public Patch takes this network-oriented image practice in another direction, forcibly rendering surveillance images into the public domain by physically affixing open license terms and conditions to security cameras and burning them onto the tape. The legalistic operationality of such images is turned inwards; as the objects in the V&A implicate themselves by association with contemporary events, so the surveillance images, intended to incriminate, incriminate themselves.

What both approaches have in common is that they are hacks in the best sense: using well-established tools – photography, street art interventions – to hijack processes illuminated and made accessible by a literacy in complex systems.

Things don’t have to be that complex, of course. There are two particular images or sets of images of computational architectures which are more traditional in form than any of the above but yet convey something incredibly powerful about the physicality and thus weighty significance of such systems.

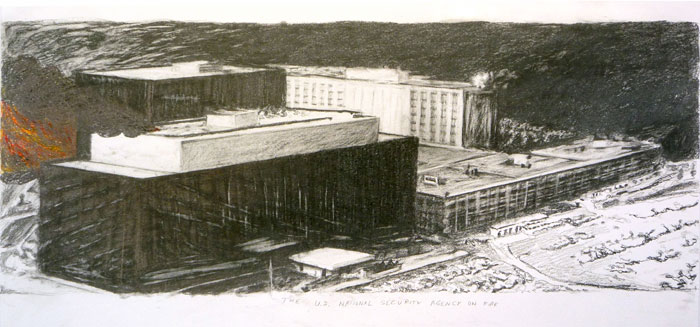

Suzanne Treister‘s The U.S. National Security Agency on Fire is definitely my favourite image of the agency, even more so than Paglen’s. It speaks to a far more direct and physical response to state-sponsored surveillance: a response involving cable-cutting and satellite-smashing as much as conciousness-raising (Treister’s work in general, through its sustained but also playful engagement with these issues, feels more successful than most at communicating the affect of surveillance and other technologies).

The other set is Simon Norfolk’s series of photographs of datacenters. Norfolk is best known as a war photographer, covering the devastation of war through its aftermath and lasting effects. His large-format images of devastated architecture and refugee camps transform ruins into monuments, and battlefields into lingering accusations.

Many of the supercomputers which Norfolk photographed are also weapons. I’ve previously deployed Norfolk’s photography when discussing “living inside the machine” and the legacy of military inscrutability in contemporary computing environments, with particular reference to his image of IBM BlueGene/L cabinets at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, busily computing nuclear detonation yields. My favourite image from the series, however, is of the Spanish MareNostrum supercomputer, housed within the deconsecrated Chapel Torre Girona in Barcelona. The MareNostrum works on medical research, astrophysical simulations, weather forecasting and other ostensibly civilian applications, but its setting seems to imply an even more elevated processual function:

I was reminded of the MareNostrum when we installed Five Eyes this week, because the stacks of archive files in their glass cabinets appeared even more like server stacks in the splendour of the V&A’s gallery than they had already in my head. It’s the lowest form of visualisation, really, paper archives for magnetic ones, but no less pleasing for it.

That is the rub, though. These equivalences, while illuminating, rarely move us forward. The necessity of forcing state changes on the intangible, of making the invisible visible and coming up with new metaphors for the essentially and materially ungraspable system of flesh, wire and emanations we inhabit is going to remain. The systems literacy which makes such visualisations and articulations possible is the pedagogical imperative of the 21st century and I fully intend to keep banging on about it. But such strategies do feel responsive rather than prescriptive, like our dull animal brains are continually struggling to keep pace with the outcomes of a world we didn’t even know we were creating, rather than working with those outcomes to structure better ones.

Here’s a thing: the visible and the invisible are products of the same belief system, and that is that all things are ultimately knowable. Wikileaks and the NSA believe the same thing: that if we can just bring all the secrets of the world to light, everything will be made good and right with the world. The museum and the software programme have the same essential ontology, that ordering things and structuring them in the right way will produce a representation so perfect we can build a whole culture atop it. But much is not knowable, and while the internet is perhaps here to reveal to us the vastness of what we do not and cannot know, the social and political philosophy with which it is mostly closely associated asserts not merely that everything is knowable, but that all things are knowable at once, and structures the world around this assumption, whether through surveillance, big data, the veneration of the market or the supremacy of the nation state. The curse of omniscience, once attributed to God, is now more tragically invested in the machine.

There is a deep and limitless unknowability at the heart of the world. This is the post-Enlightenment realisation engendered by our new technologically-mediated viewpoint (“post-” understood not as “the successor to” but “the crisis of”). Its immanence in the network cannot be rationally denied for much longer: as artists it is what we have been scratching at forever. The challenge is to implement and operationalise this understanding, to historicise and politicise it, to not be content merely with visualising and materialising what we cannot see, but to radically rethink our understanding of what we, as actors and agents, artists and citizens, states and systems, can ever see at all.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.