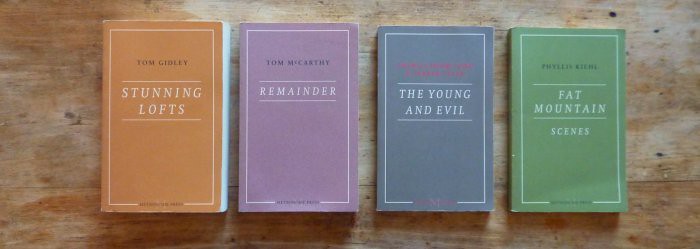

I’ve written about Metronome Press before, in a series of articles at the old STML Litblog in 2005 – 2006. If you recall, the Metronome series commissioned contemporary artists to write novels, presented as much as art pieces or artefacts as well as traditionally published books. At least one of the authors, Tom McCarthy, has gone on to considerable success in the mainstream.

What I most liked about Metronome back then was twofold: the unashamed presentation of such work as “art”, and the appropriation of the mundane apparatus of the art world for the funding, distribution and publicity of literature.

Metronome’s paperback series was sponsored by a series of patrons who were named in the back of the book. These included private individuals and arts organisations, private as well as state (being based in France, there’s rather more scope for the latter than in our own, arts-impoverished corporate politics). And the works were very clearly curated, emerging from a personal relationship between curator (editor) and artist (writer), in the service of a commission. (The exception being Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler’s The Young And Evil, an immaculate resurrection of a text first published in 1933.)

Curation, commission, patronage: terms rarely heard in literature, and literature is the worse for it.

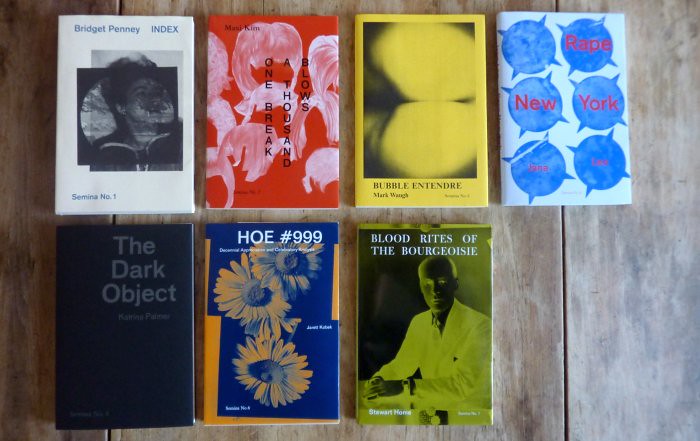

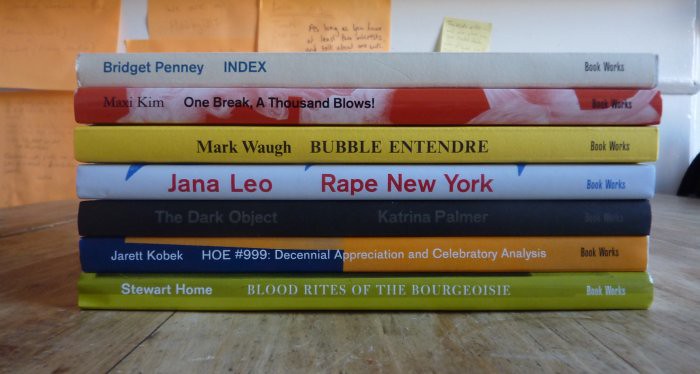

One attempt to change this has been going for a while now, and has just released three new works, bringing the series total to seven: Bookworks‘ exemplary Semina series. I’ve written about Semina before too, but it bears repeating for this occasion. The text of the original call for submissions makes the series’ intentions clear:

Semina takes its inspiration from a series of nine loose-leaf magazines issued by Californian beat artist Wallace Berman in the 1950s and 1960s. We are looking for artists and writers interested in experimental prose fiction, who transgress all the boundaries separating art and literature. Think of the ways in which Paul Gilroy theorised the history of modernism through the rubric of the Black Atlantic, W.E.B. Du Bois and double-consciousness, and the inescapable links between race and class: Anthony Joseph, Kathy Acker, Amiri Baraka, Samuel R. Delany, Darius James, Ishmael Reed, Ann Quin, Clarence Cooper Jr, Claude Cahun etc. Above all we’re looking for artists and writers willing to take risks with their prose and who demonstrate total disregard for the conventions that structure received ideas about fiction. […]

Editing is expected to be a collaborative process between the editors and the commissioned artist/author, with the aim of producing a text sympathetic to the ambitions of the series. The editors would expect to work closely with the commissioned artist/author on any redrafts and revisions. You will be consulted at each stage of the process and expected to help take decisions about the way in which the work is presented in book form.

The series has already produced at least one masterpiece, in the form of Bridget Penney’s Index. Penney is exactly the kind of writer best served by the curatorial/patronage approach: previously published (by Polygon, in 1991) but little known outside enthusiastic artistic circles. The work was completed over a number of years, and brought to publication with the encouragement of series editor Stewart Home (a conversation between the two is available on Home’s site).

The three new novels released this week are The Dark Object by Katrina Palmer, HOE #999 by Jarett Kobek, and Blood Rites of the Bourgeoisie by Home himself, a sample of which can be found in Wednesday’s Mattins.

A new work by Home is always cause for celebration. I was lucky enough to publish his last book, Memphis Underground, in 2007, but this isn’t log-rolling: I’ve been a fan of his work for much longer than that. Home is one of a class of writers fated to stay with each of his publishers only briefly, badly served and frequently misunderstood by critics; yet, he continues to produce work and to see it published (even when, as has happened, he resorts to trickery in the small ads), while moving (un)easily between the worlds of literature and art. Such a position makes him eminently suited to the position granted him by Semina: editor, curator, contributor and collaborator.

The type of work produced by Semina, and Metronome before it, and their inspirations before that, will never reach a mass audience, and they should not have to. But their literature is vital, buoying up and sustaining a complacent and frequently dull literary culture. We could learn much from the auteurs of the art world.

This site made me start wondering, now that e-books will reduce the number of real books, whether the physical appearance of the real book will take on even more importance.

Comment by Shelley — July 13, 2010 @ 9:16 pm