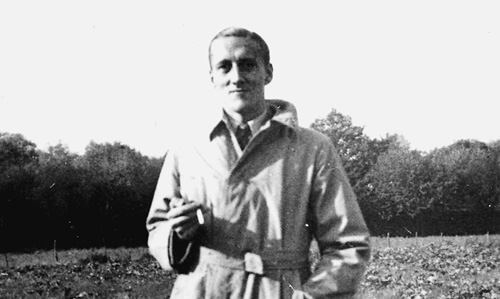

As a little end-of-year project, I’ve just launched jocelynbrooke.com, a site dedicated to the life and work of English writer Jocelyn Brooke (1908—1966). I’ve become somewhat obsessed with Brooke in the last few months, and have begun a small campaign to revive his reputation.

Brooke’s writing, which clusters in the decades around the Second World War, is unique in English letters. I’ve managed to amass an almost complete set of his books with a particular penchant for the Kafkaesque Image of a Drawn Sword and the angst-ridden The Scapegoat, and extending to his delightful botanical treatise The Flower in Season, and his extraordinary Surrealist work of 1956 The Crisis in Bulgaria, or, Ibsen to the Rescue! His semi-autobiographical novels are works of a rare quality, combining a deliberately Proustian longing for things past with a very English melancholy and sense of place, and a sensual quality that feels quite out of its time, and which is deeply rooted in his private and currently little known life. I can’t recommend them highly enough.

Brooke’s works are currently in a kind of limbo. I approached the agents for Brooke’s estate several months ago with a view to acquiring the rights to republish several of his works, as some of the lead titles of a new imprint launching later this year. Although I was initially informed the rights were available, it subsequently appeared that Faber, in the form of their ‘Finds’ POD imprint – who are already republishing Brooke’s Military Orchid trilogy – have expressed an interest in the other books as well.

While I’m pleased that anyone is interested in republishing these works, anyone who knows my opinion of Faber Finds won’t be surprised that I’m deeply opposed to this – and not for entirely selfish reasons. Faber Finds, while a great way to get little-known works back into print, does no promotion of the titles on its list, and there is no way that Brooke will find a new audience through this method. As time passes, it becomes harder and harder to revive a writer’s reputation, but it can be done: see the recent renaissances of B.S. Johnson and Julian Maclaren-Ross. For this to happen to Brooke, he needs to be republished properly, and promoted.

Conflicts between long-tail POD databases like Faber Finds and true classics republication are only going to increase, and Brooke’s agents are currently considering their position on POD and the way they license rights. I hope I get the opportunity to work with and increase the readership of Brooke’s outstanding work, and in the mean time I’ll crack on with jocelynbrooke.com.

Happy New Year.

Can you expand on Brooke’s “deliberately Proustian longing for things past”?

I ask because Proust’s novel does not, as far as I can recall, express any particular longing for the past. It evokes the experience of regaining time past, time lost, yes, but is nothing to do with lush nostalgia. Perhaps I’m being picky because Proustian has long been pigeonholed, mainly because of the Shakespearian mistranslation of Moncrieff’s original title.

Comment by steve — December 31, 2008 @ 6:44 pm

A little picky I think – longing, in the sense of a strong persistent yearning for something unobtainable – not necessarily the past itself, but the experience and sensations of it – is a large part of Proust and Brooke for me. Perhaps another, more critical, term would be better, but hey, it’s New Year’s Eve.

Comment by James Bridle — December 31, 2008 @ 6:55 pm