This morning, on as wet and dismal a Tuesday as London has to offer, I had the pleasure of meeting Bibi Bakare-Yusuf and Jeremy Weate from Cassava Republic.

Cassava Republic was founded four years ago in Abuja, Nigeria, with the intention of introducing African readers to local writers too often celebrated only in Europe and America, and to encourage home-grown writing, “rooted in African experience in all its diversity, whether set in filthy-yet-sexy megacities such as Lagos, in little-known rural communities, in the recent past or indeed the near future.”

Cassava faces all the usual pressures of a small publisher in a developing industry: poor or almost total lack of design, typesetting and printing services, non-existent distribution channels, a lack of an established network of booksellers and readers. All their books are designed and typeset in the UK, despite the added costs this brings, and printed in India. Sales reps spend most of their time in coffeeshops and hairdressers, where the real book sales occur; traditional bookstores are dingy, unfriendly places which trade almost exclusively in the textbooks and government publications that make up the overwhelming majority of the African market.

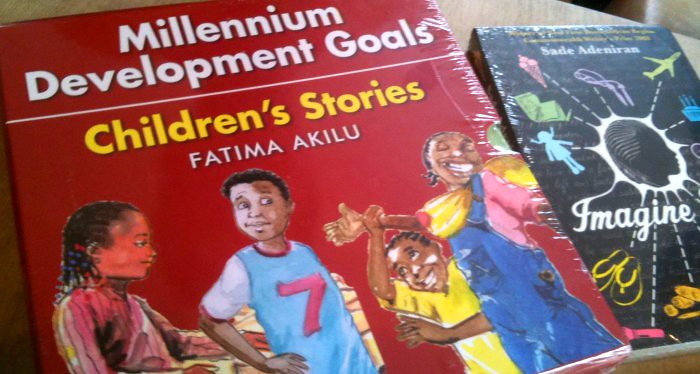

Despite these challenges, Cassava has had a number of successes, not least with childrens’ books. Their specially-commissioned collection of stories by Fatima Akilu sets seven stories to accompany the United Nations’ 7 Millennium Development Goals. Many Nigerian children grow up without ever seeing a picture book; for most of those that do, the stories will be alien to them the characters will not look like them and their lives will not resemble theirs. Akilu’s stories give those children real empowerment—to girls as well as boys—as well as opening up the possibilities, for Cassava, or developing and licensing the characters further.

Internet access, while still in development in Nigeria, is expanding rapidly, thanks to physical infrastructure. Previously the whole country was served by a single government-funded undersea cable. A new, privately-owned cable landed just last week, promising to increase Nigeria’s connected bandwidth twentyfold, with several more cables due in the next few years. Over 1m Nigerians use Facebook, and Cassava are eager to exploit this increased connectivity to reach readers who have not yet explored local and Pan-African writing.

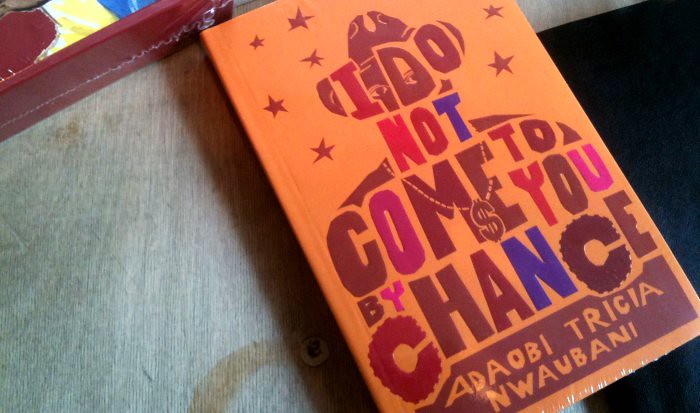

Contemporary Africa is particularly present in Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come To You By Chance, which tells the story of Kingsley, a young man eager to help his family and change the world. “When his once-proud family descends into poverty after his father falls ill, he is forced to turn to his mother’s infamous brother, Cash Daddy, who runs a successful empire of email scams relieving gullible Westerners of their hard earned money.” I can’t help (because I’m slightly obsessed) but be reminded of Chetan Bhagat’s One Night at the Call Center, because it points to a publishing model which engages with the lives of real, young people now, in their localities, rather than reaching out to a foreign audience, and in return, holds out the possibility of uncovering a wholly new and untapped market.

Like the small example of African Science Fiction, the future of all publishing in Africa promises new business models, new approaches to readers, and new literatures. What an exciting future.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.