I recently spent four weeks as Artist in Residence at the Visible Futures Lab at the School of Visual Arts in New York, a guest of the MFA Interaction Design and Products of Design courses. I made a drone recognition kit.

This kit consists of three models of contemporary military drones: the MQ-1 Predator, the RQ-170 Sentinel, and the RQ-4 Global Hawk. Human figures are included for scale.

The kit was produced using 3D modelling software and desktop 3D printing technologies, with the assistance of Digital Fabrication Specialist Carlos Cruz.

All three UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) depicted here are in use at the present time to provide situational awareness in conflict zones around the world for a number of armed forces, as well as in domestic use, including border patrol, forest fire and storm observation, and humanitarian relief. These three UAVs are all configured as unarmed surveillance drones, although they may be weaponised.

The kit is based on military and civilian recognition kits: collections of models used to train gunners, radar operators and visual observers.

When I was 15 or so, I spent a week on an army cadet camp in the UK. One day, I saw Gurkha soldiers lying down in the grass with handbooks and binoculars, while an officer, twenty feet away, took small, inch-long lead models of tanks from a chest and placed them on a mound twenty feet away. They were practicing tank recognition and identification. This image has stayed with me ever since.

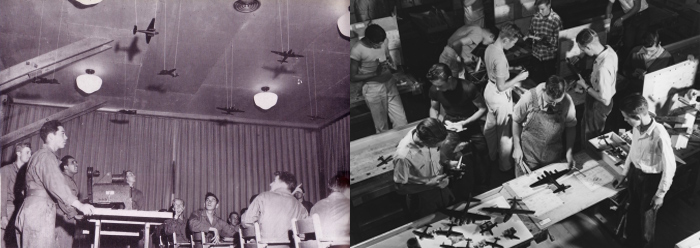

Models for aircraft recognition and targetting have a long history. Ever since the development of aircraft, there has been a parallel industry in visualising, representing and observing such vehicles, often on the basis of scant information. The wars of the twentieth century made such artefacts vital. Between 1942 and 1945, schoolchildren in the US, Canada and South America assembled hundreds of thousands of aircraft models for this purpose. (The Friend or Foe? Museum maintains an extraordinary collection of such materials centred around the Second World War, from which the images shown below are taken.)

There is also a long history of civilan observation worldwide. The Ground Observer Corps in the United States employed over a million civilians at the height of the Second World War, while the Royal Observer Corps in the United Kingdom, founded in 1925, deployed tens of thousands of civilian personnel during the same period, across a network of 1,500 posts, including one atop Windsor Castle. The latter were only stood down in the 1990s.

Models are still employed for recognition training today, as well as for strategic planning, battlefield, airfield and carrier management, and design testing. Meanwhile, the actual aircraft become ever harder to perceive. Based at remote airfields in conflict zones, and largely operating in other zones inaccessible to ground troops or journalists, the only direct witnesses to their activities are those on the ground beneath them, disconnected from those who pilot them, those who issue their orders, and those in whose name they are directed.

The Kit is a continuation of a range of projects, which include my work on making evident the processes of technological production, as well as the more explicit Drone Shadows and Dronestagram.

The UAV Identification Kit is an act of visualisation, a materialisation of an unseen technology. As our technology grows ever more networked, ever more complex and interconnected, it both brings us together, and distances us. What we choose to do with these technologies is a function of our ability to see and read them, and to act with them: a literacy, a fluency, and an agency.

The Kit is intended to confer and facilitate these things, training the observer, enabling them to bear witness, and to act.

I have written more about this project on another ongoing research blog. In particular, there is a post about the modelling and printing process, and the material traces of 3D printing, and a post about vernacular models, representations and photographs of drones.

More pictures of the kit, and the process, are available at Flickr.

Many thanks again to SVA, and particularly to Leif Krinkle, the director of the VFL, and to Carlos Cruz.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.