Following the release of Rorschmap, which has received over 150,000 visits and been written about (thank you) all over the web, I was made aware of or discovered many similar works, only occasionally accompanied by legal threats.

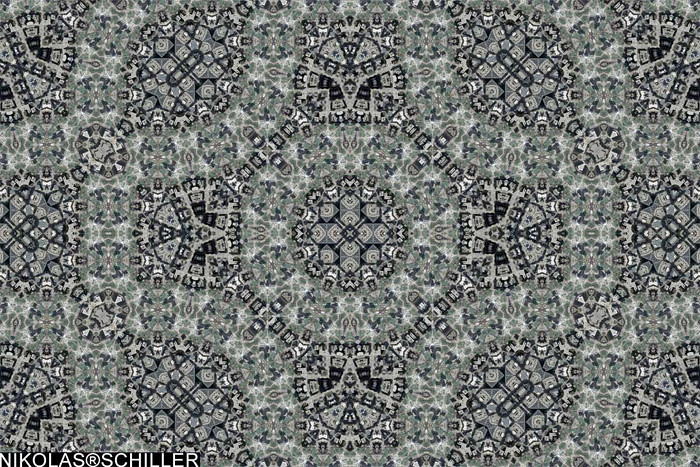

For example, here are the Geospatial artworks of Nikolas Schiller:

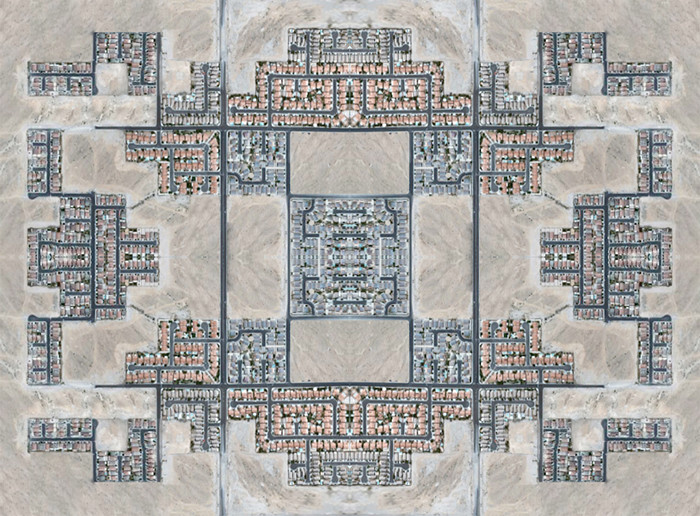

And the “WorldWide Carpets” of David Hanauer:

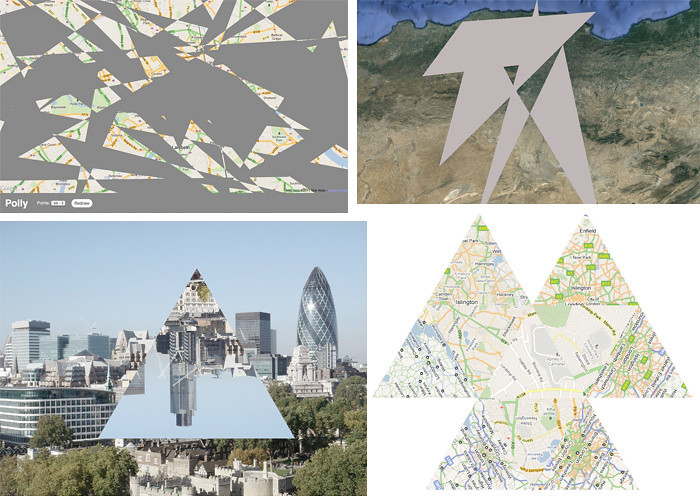

There are a lot more out there: the Rorschmap is not a globally novel conception, although it was entirely new to me. It emerged organically from my investigations at the New Aesthetic and followed a huge range of experiments with maps and map data/APIs, many of them documented on Flickr:

This post is not about justifying my version of the Rorschmap, or claiming ownership of it in anyway: I have no interest in doing that. That said, certain claims have given me a greater sympathy for people, like Daniel Horowitz, accused of plagiarism. Shapeways’ recent blog post on simultaneous invention is worth a read. Things are speeding up, the internet is flattening time, we see further, everything is simultaneous.

What I am interested in is how my Rorschmap differs from those other instantiations. What I am interested in is how digitisation changes not just the format of a thing, but its fundamental essence.

These other images, while made possible by digital maps, could have been created with physical, paper, maps in much the same way. The Rorschmap is wholly digital, web-based, interactive. Its interactivity seems to be key: the first response of almost every visitor is to look up their home or another familiar place. Art customisation. I’m not sure how it could be shown in a gallery, for example, without simply installing a web terminal.

This echoes a debate currently raging in the web art world. At this year’s Armory Fair in New York, Rhizome director Lauren Cornell offered digital artworks for sale, promising that “you can sell digital work in different ways but in Sara’s case we’re going to take it offline for the collector so they can just have it locally.” Artinfo.com has the full story, but the reactions have been varied and frequently vociferous. “If a digital file is not live on the Internet, is it still a work of Internet art?” is one response; the hacker promise that “We will get that art back online by any means necessary” is another. I have no strong feelings about this, because the way I see it, if a digital file can be taken off the internet, it is not Internet art.

An answer, perhaps, is that the difference is systems. While the fixed maps are products of the system, the Rorschmap can only exist as part of the system, the network; indivisible from of it, composed of it. Holographically embedded in it. In the great undesigned, unintended coral reef of the web, artworks are not products, but systems. The social book is not a product, but a system, in which author, publisher, reader and increasingly a host of services, collaborate in an experience. This, less the services, has always been the case, but the culture is increasingly wired into the network, irrevocably entangled.

Digitisation makes something ephemeral, reproducible, robot-readable—and networkable. In fact, its capacity to be connected to other things like and unlike itself is its most insistent quality. It longs for it. The digital object is immanent in the network. It is where it is most truly itself, which is everything.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.