For some time, I have been threatening to write about the Render Ghosts. I was asked to contribute something to Electronic Voice Phenomena, an online literature and art project by Mercy and Penned in the Margins, and so I wrote about my recent trip to New Mexico, in search of the Render Ghosts:

I first noticed the Render Ghosts on the hoardings surrounding a new development near Finsbury Square. On the balconies of some vast, virtual tower, two pixelated figures looked out over a darkened London, a perfect red-pink gradient sunset behind them. He had short dark hair and stubble, wore a black jacket and blue jeans. She had a cropped red bob, white jacket, and a purple knee-length skirt. I didn’t know who they were, but I started seeing them everywhere.

Read the full piece over at EVP.

I also have a short essay and illustrations in the wonderful new Visual Editions‘ book of writing and maps, Where You Are, which also includes contributions from Joe Dunthorne, Geoff Dyer, Olafur Eliasson, Sheila Heti, and more.

To ask “Where You Are” invites a series of responses: cartographic, historical, social, spiritual, situational; discursive or prescriptive. The GPS system is a monumental network that provides a permanent “You Are Here” sign hanging in the sky, its signal a constant, synchronised timecode. It suggests the possibility that one may never need be lost again; that future generations will grow up not knowing what it means to be truly lost.

The book is available to order now, but you can read the essay, and see the illustrations (much beautified by the designers at Bibliothèque), alongside all the other contributions on the Where You Are website.

The astute among you might notice a strong similarity between the diagrams in Where You Are and the piece I made for Container some months back:

This 3D-printed object is the same thing under discussion in Where You Are:

This is a model of the Global Positioning System (GPS), a constellation of 24 satellites, in six orbital groups of four satellites, each orbital plane at 55 degrees inclination, and 60 degrees right ascension to its neighbour, 20,200 kilometres above the surface of the earth; a machine we are all living inside.

I’d had the original model sitting on my desk for some time before Tim asked me for a contribution to Container. In trying to draw and understand the GPS system as an abstract machine, I’d modelled the constellation in Sketchup – it was a natural step to flip-flop this nest of intersecting cones of influence back into the physical realm again, so that I could roll it between my fingers, as Einar and I did with airfix models of the drones, before the shadows (Einar’s own thinking about GPS, with Timo and Jørn, led to the Satellite Lamps project.) I call this the “Close Encounters” method.

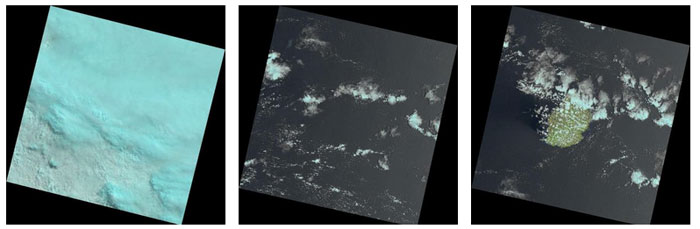

A while back, I started the Laaaaaaandsat tumblr, which automatically posts, several times a day, every image released by the USGS Landsat observation programme – an ongoing, comprehensive survey of the planet by another satellite, 700km above the earth’s surface.

The endless stream of off-kilter images – reoriented so North is ‘up’ – remains a endless source of pleasure. So when Aperture magazine asked for 200 words on “What Matters Now” in photography, I thought of this little robot cameraman in the sky. 200 words is not enough, but it’s in the new issue.

NASA’s Landsat is the longest-running program dedicated to photographing the Earth from space, and has created millions of images since its inception in 1969. The first satellite, Landsat 1, was launched on July 23, 1972, atop a Delta 900 rocket from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Its mission was to photograph the whole Earth using three cameras which see both visible light and the near-infrared, and a four-channel multispectral scanner. The scanner was the project’s greatest innovation as it reveals hidden details about the planet’s surface, producing data and imagery used for everything from disaster relief, to agriculture, to studying climate change.

In February of this year, the program continued with the launch of Landsat 8. This incarnation features a more powerful scanner which sees in the ultraviolet; the panchromatic; the shortwave, near-, and thermal-infrared; revealing the presence of dust and smoke, of chlorophyll, of sub-surface rock formations, and the shape of clouds. The satellite captures four hundred images every day, creating a complete picture of the planet every sixteen days. Every one of these images is in the public domain, allowing every one of us to use, benefit from, and marvel at this ever-growing, ever-changing automated portrait of our planet.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.