(On light: the title is taken from Kei Miller’s A Light song of Light, which says all of this so much better.)

One of my favourite artworks in the world is Michelangelo Pistoletto’s ‘Cubic Meter of Infinity‘, which I first saw in Tate’s Arte Povera exhibition about ten years ago. It consists of a box made of inward-facing mirrors, and it bends the mind. If there is light in the box, it must be infinite, but if there is no light, what is reflected?

I thought of Pistoletto when reading Andrew Blum’s Tubes, on the physical infrastructure of the internet. Of the millions of miles of light transmitted through fibres beneath the sea and street, sheathed in black plastic, invisible to the eye, visible only at the point of transformation or repetition, a light that illuminates at a distance.

I was reminded of Pistoletto, again, last week, at “Pacific Standard Time”, an exhibition of Southern Californian art, 1950-1980, at the Martin-Gropus-Bau in Berlin. Larry Bell’s ‘Untitled, 1969’ is another metre cube: this time made of smoked, semi-reflective glass, only just transparent, so that one sees oneself reflected in it, other patrons through it, and shards of other works, like Hockney’s ‘Bigger Splash’, hung on a nearby wall. It is a ghost cube, hovering somewhere between Pistoletto and Anish Kapoor, who has made pieces that both fully reflect (the Cloud Gate, ‘Turning the world inside out‘), and absorb (the black pigment pieces). Gerhard Richter too, currently on show at the Neues Nationalgalerie and formerly at Tate, whose glasses break down the outline of the viewer, turn them into one of Richter’s own paintings.

James Turrel’s ‘Stuck Red’ and ‘Stuck Blue’, also in “Pacific Standard Time”, fill voids in the wall with intense fluorescent light, so that they appear to be flat panels of light on the surface of the wall, instead of inside it. He has everted notional space.

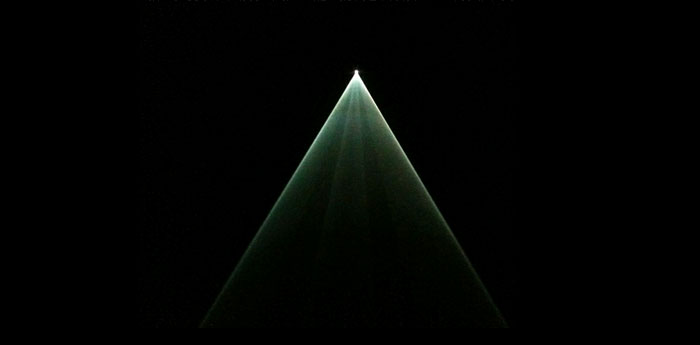

Anthony McCall’s light hazes at the Hamburger Bahnhof, at P3, at ACMI. Locator beams, like the superstructure of GPS, a vast mesh tent enclosing the earth, 20,000 km above the terrestrial net. Radio waves are just invisible light.

At the Berlinische Galerie, an exhibition of Boris Mikhailov’s photographs from Ukraine, before and after the fall of Communism. These were originally presented as slideshows, as light, and many are coloured: coloured in, or washed in blue or sepia tones:

“… the brown sepia tone. This colour lends the work a historical and even nostalgic quality. The aesthetic evokes memories of early photography and engrains a sense of history into these pictures.” (Wall panel, Berlinische Galerie, emphasis mine)

Photography is made of light, capturing and projecting it. Classical photography contains a double projection: the world onto the film, the film onto the print. Digital images are captured more directly, onto the CCD, and printed with pigment, rather than light; but then they’re hardly printed any more: instead, they are continually projected from the screen, back at us. They are light all along.

Analogue photography rendered the light physical. In contrast, digital photography preserves the illumination. Re-projected, illuminating at a distance.

(Berlin is the original home of Bring Your Own Beamer, a series of exhibitions hosting artists and their projectors. The most striking image of Occupy Wall Street was the projection on November 17th of slogans onto the Verizon building, as thousands marched across the Brooklyn Bridge. London’s Olympic Games Act of 2006 grants Police specific powers to enter private properties and seize material and equipment that might be used for projection. Reclaim the light.)

(Another work from that Arte Povera show: Giovanni Anselmo’s ‘Invisible’, an out-of-focus projector, which, when the viewer inserts themselves into its field, reveals the word “Visible” displayed on their chest. I recalled the message, incorrectly, as ‘Hello’; the effect is the same. Waving at the machines.)

In Alan Moore’s “Century” series of “The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen”, he crosses the streams. Jerry Cornelius appears, inverted, in black and white: “I’m feeling very negative at the moment.” And Iain Sinclair appears (ad parÄ“re) as Norton, the prisoner of London, doomed to exist in all Londons, through time and the city, to see every connection and emission, but unable to leave or intervene. I think Sinclair might have been practicing Network Realism for some time—his network the city, of course, strung together with light, the beaded ropes of Albert Bridge, the brash glow of Piccadilly Circus, the Maian eyes of the City and Canary Wharf.

I think of a line by my friend Jennifer, who has worked on the New York Times app and hand-made artists’ books, and says the only difference between the two is “the velocity of the material”. I think that the physical and the digital are inseparable in culture in the same way that waves and particles are inseparable in light. I think the network permeates all things, is an extension of the eye, which is an extension of mind. It is all made of light.

[…] This is great, and reminds me how Berger-esque some of James' art-writing is getting. […]

Pingback by Infovore » Links for May 16th — May 16, 2012 @ 2:00 pm