TL/DR: I made a film and exhibition about flamingos, migration, and the history of radar for Drugo more (Rijeka, Croatia), travelling to Ljubljana next February. More information on their site, and on mine.

At the end of last year, I spent a couple of weeks in Cyprus as a guest of NeMe in Limassol. The trip was part of the State Machines programme, an ongoing, two year collaboration of five independent institutions around Europe investigating “art, work, and identity in an age of planetary-scale computation” – or, in my shorthand, what digital tools enable individuals and groups to do which only states could do before. The programme has developed multiple travelling exhibitions, conferences, publications, and opportunities for artists, including Transnationalisms, an exhibition I curated in Rijeka and Ljubljana.

In Cyprus, I was supposed to be investigating the international trade in citizenship, and particularly the Golden Visa programme, which allows people with sufficient funds to buy their way into Europe. I did do that, and I wrote up a lot of that research in an essay for the Atlantic, and I met all kinds of interesting people along the way, including artists working across the complex border zone between the two halves of the island, Russian émigré’s setting up blockchain-based nations, and FOREX traders using machine learning to target clients around the world. But I also found myself in a strange territory which I was previously aware of, but had never really thought about, and which became the basis for a recent solo exhibition in Rijeka, Croatia (and which will travel to Ljubljana in February).

When Cyprus gained independence from Britain in 1960, it signed a treaty giving up control of some square 254 km of the island in perpetuity, which became the two Sovereign Base Areas – British Overseas Territories which remain under the control of the British military to this day. And – as in the British Indian Ocean Territory, another weird bit of geography I’ve written extensively about before – they are shared extensively with the United States as well, with a long history of surveillance and communication usage alongside their territorial advantages.

One of the Base Areas is called Dhekelia, and sits hard up against the border with Turkish-controlled northern Cyprus, along the line established following the invasion of 1974. If you drive this way from the Republic to the town of Famagusta in the North, you pass along a road which is Cypriot on the one side, Turkish on the other (nomenclature is hard here – don’t @ me), and British beneath your wheels – as well as being lined with the occasional UN guardpost. You can see the border – the yellow line – in the above image.

Inside the territory on the right of that image is Ayios Nikolaos Station, the largest GCHQ listening station outside the UK, which is part-run by the NSA. In the Snowden documents it’s referred to as SOUNDER, and is used for satellite and radio interception, as well as tapping the many fiber-optic cables that carry the internet across the Mediterranean. You can drive past the dishes and antennae on your way to Famagusta, and plenty of people live and work there, but there are huge no-photography signs and the British military police will take an interest if you linger.

At the other end of the island is the second Sovereign Base Area, RAF Akrotiri, which is separated from the city of Limassol (top right, above) by a huge salt lake. Again, the base is a joint UK/US operation, and in recent years has been a base for airstrikes on Libya and the Islamic State, as well as other operations. One early morning when I was out on the lake, a U-2 “Dragon Lady” of the 9th Reconnaissance Wing took off directly over my head, one of the loudest sounds I have ever heard.

As well as the airfield, Akrotiri is home to another vast antenna and radar field. These antennae include, it is understood, more interception capabilities as well as over-the-horizon radar capable of watching distant airspace. Although the whole peninsula is British sovereign territory, only the air base is off limits to visitors, and the radar site is plastered with all the usual warnings against stopping your car or taking photographs. But the salt lake is also one of the most important wetland areas in the Mediterranean, home to tens of thousands of migrating birds every year, and as a result there are plenty of birdwatching spots.

The lake is home to up to 20,000 greater flamingos every winter: strange, beautiful birds which are deeply comical until you spend time with them, when they become deliberate, elegant, and fascinating. I was supposed, I thought, to be watching the radars, but I ended up watching the flamingos instead.

Back in the 1940s and 1950s, the first users of radar systems encountered various strange effects. RAF operators of the new technology would report shimmering lines moving across their screens, and scramble fighter jets to intercept what appeared to be vast waves of incoming bombers, only for the skies to be found empty and the signals to fade away. Over time, these ghostly signals came to be known as ‘angels’.

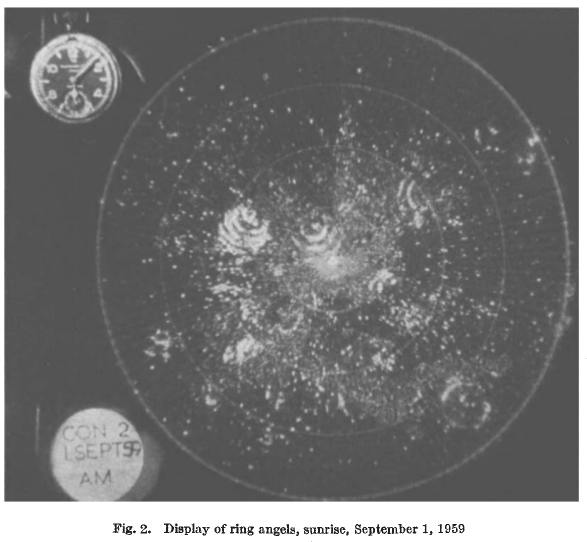

The source of the angels remained disputed for some time, and was complicated by the appearance of further patterns, such as the ‘ring angels’ shown above, which resembled the ripples of stones dropped in water. The caption is a giveaway, but it was a couple of decades before it was generally agreed that these patterns were caused by birds.

It took some time for this idea to take hold, and was much resisted, because radar revealed a whole host of things about birds which had not been previously known. For example, the wartime RAF had a saying that “Only birds and men fly, and birds don’t fly at night” – as was widely believed at the time. But today we know, largely thanks to radar, that most bird migration takes place at night.

In one of those strange quirks of wartime employment, a number of leading ornithologists of the time ended up working within the radar group – notably David Lack, later director of ornithology at Oxford, who was assigned to the Army Operational Research Group in Orkney, and in 1945 co-published the first paper in the field of what would become known as Radar Ornithology. The sudden visibility of previously unknown phenomenon opened up whole new areas of research in the natural sciences. (There’s a great dramatisation by the BBC of Lack’s radar discoveries available online.)

Following my time with the flamingos in Cyprus, I started learning more about the birds, and migration in general. I got in contact with the Tour du Valat, a biological research station in the South of France, which has been monitoring flamingo populations around the Mediterranean for more than forty years. Tour du Valat was one of the very first research centres dedicated to wetland conservation, and the driving force behind the Ramsar Convention, one of the first international environmental treaties.

Flamingos, it turns out, are pretty interesting. They are extremophiles: they have special glands for excreting excess salt which allows them to live and feed in environments toxic to many – and which will become more widespread as climate change renders the oceans more salty, and sea level rise drives salinity inland. They can live for four decades or more, and are constantly on the move, capable of flying at up to 60 kph and have been known to travel over 500km in a single night between habitats. They form lasting pair bonds, but also swap partners in large colonies, and are well-known for same-sex partnerships.

The researchers at Tour du Valat were kind enough to share some of their data with me – a vast database, in fact, containing some 600,000 sightings of more than 20,000 individual birds. It’s an extraordinary document, and I had to write my own tools to start to explore it, to pull out the histories of individuals from this array of information. Below, for example, is a simple and very far from exhaustive map of the sighting locations of a single bird, tagged in 1985 with the ring number ABDF, over thirty-seven years:

The researchers were also at pains to make me aware of one aspect of these data that is little acknowledged in the field – although it’s of much concern to critics of technology and others – which is that digital data of this kind is inherently reductive, and driving a trend within ecological studies which many are uncomfortable with.

In the early days of the natural sciences, specimens were captured in the wild and then brought back to sites of learning where they would be compared and classified, integrated into the systems of knowledge then under construction. The result was the grand edifice of twentieth century categorisation, which sought to place every organism within a tree of life, each distinct and fixed. Reacting to this, the ecological movement has sought, since the 1960s, to return life to the world: to emphasise the interaction between species and their environments, and the encounter of the observer with what they recorded. “Big data”, in the form of vast databases which attempt to synthesise all of these gathered records, has turned this idea on its head once again, and that which is outside the database – the name of the observer, the weather on that day, the lived experience, the undocumented and the ephemeral – vanishes once again from view.

I was recently invited to show work related to the State Machines project at Drugo more in Rijeka, Croatia, and all of these various influences ended up being part of the exhibition. Above is a snapshot of Catch and Release, a two-channel installation which explores the Tour du Valat database, transforming lines of anonymous data back into tiny stories of actual encounters – and erasing each line as it goes. The short stories are accompanied by “rorsched” satellite images of the actual locations – a technique I keep returning to as a way of communicating the beauty but essential unreality and inaccessibility of this kind of remote, mediated image-making.

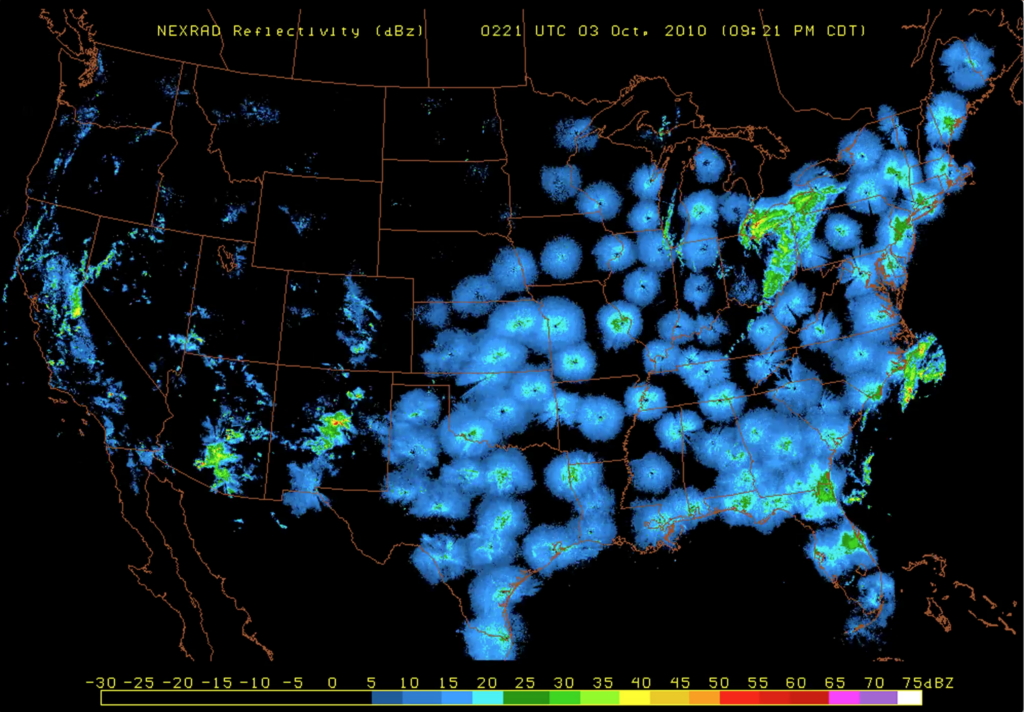

Alongside this work was exhibited live twelve-hour loops of radar data from US weather installations, in which, at dawn and dusk, crackly contemporary ring angels are visible (I did write to the base commander at Akrotiri and asked how often the flamingos appear on their radar, and whether I could see some data of this, but they told me that it was not possible for them to comment).

I also took ABDF, the flamingo mapped above, and wrote out a longer text for him, which engaged with his own travels to half a dozen countries around the Mediterranean, as well as the complex histories of colonial and industrial exploitation, climate change and population dynamics which are entangled with the region, and all its human and non-human inhabitants.

The final piece of the show gave it its name: My delight on a shining night, a thirty minute film documenting the flamingos of the Limassol salt lake, and their environment, which includes the antenna and radar arrays. (Contrary to my usual practice, I’m not posting it online, as it’s long, meditative, and unsuited to small screens.)

From the mid-1970s until 2008, Akrotiri was the broadcast site of a numbers station known as the Lincolnshire Poacher, for its use of the opening bars of the English folk song of that name as its callsign. Numbers stations are radio broadcasts which endlessly repeat number sequences, presumably as messages to spies and other covert units, which were widespread during the Cold War, and the Lincolnshire Poacher was among the best known (you can listen to an excerpt here).

The original song is an exuberant paean to the joys of stealing game from the properties of rich landowners, and getting away from the gamekeepers:

As me and my companions were setting up a snare,

Listen to an archive recording from the British Library

The gamekeeper was watching us – for him we did not care,

For we can wrestle and fight, my boys, and jump o’er anywhere.

Oh, ’tis my delight on a shining night, in the season of the year.

The film contains recordings of both the numbers stations and the original song – as well as footage of the flamingos themselves, these strange, beautiful, extremophile creatures living among the detritus of our power games and industrial waste. The ground shifts, as I watch it, between the shimmering infrastructure of control and surveillance and the exuberant life of the birds and ourselves, between information and ecology, between computational prediction and embodied observation.

I’ve spent so much time around these military technologies and surveillance strongholds, documenting abuses of power and systemic violence, and I find myself constantly drawn back to them – while glimpsing, every time, the wider ecological systems in which they exist. I’m reminded of those telescopes which the National Reconnaissance Office quietly turned over to NASA a few years ago: what would it mean, taking radar ornithology as a guide, to turn the extraordinary powers of our technology to the service of nature, rather than its destruction?

In talking to conservationists around the Mediterranean basin, one thing is obvious: they are more clear-eyed than any tech reckoner or political strategist about the future: a future of rising sea levels, hotter and wetter weather, and more extreme events, climatic and political, for all of us. And this narrative, whatever local effects it might entail, seems inevitably to involve the collapse of our technological infrastructures, created to give us protection from and mastery over the environment, back into the world which they so often attempt to deny or control. We are going to have to think carefully about what we choose to look at, and what we choose to see through these various, complex, and compelling lenses we have built ourselves.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.