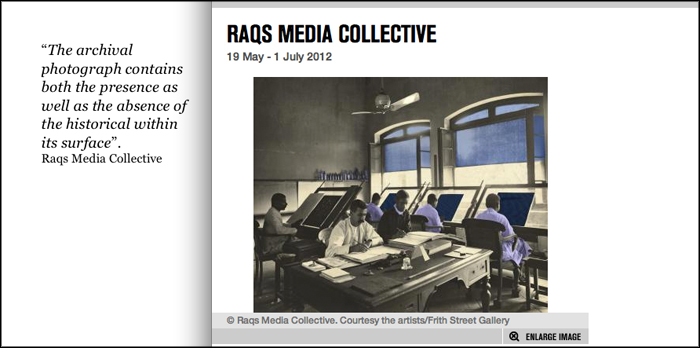

At the Photographer’s Gallery in London last month, Raqs Media Collective presented An Afternoon Unregistered on the Richter Scale (2011), a large-scale (wall-filling) video piece, an animated photograph. The original image showed clerks at work in the ‘Examining Room of the Duffing Section of the Photographic Department of the Survey of India’. It was taken in 1911 by British photographer James Waterhouse. It is an upper-basement room: men work at large desks, poring over maps. The pencilled note on the back of the original photograph reads:

Duffing Section. Examining Room. Every negative that corrected proof & colour patterns before being sent in for printing. This is the room where the duffing was carried out in your time. Mr Vieux at the desk, he is Head Asst. in charge of this section.’

Raqs Media Collective gently animate the photograph. Over the course of ten minutes or so, a fan turns lazily overhead, pages riffle in a breeze, the light brightens and dims, a man walks past an open window. So softly. The lazy heat of a warm afternoon in Calcutta, 1911.

“Duffing” is a process of correction in manual cartography. Lines for printing are first inscribed to form a negative, digging crisp lines into a thin material with a metal or sapphire-tipped scribe tool. Where corrections are required, the sheet is rewashed in a duffing liquid, and the lines are re-inscribed. A separately inscribed sheet is required for each printing colour: the Raqs illustration is bathed in blues and purples, the colour of memory and melancholy.

The Survey of India remains one of the largest single mapping undertakings in history. For much of the Nineteenth Century, it was occupied with the Great Trigonometric Survey, the first complete mapping of the subcontinent, responsible too for measuring the heights of the Himalayan mountains, and the first accurate measurements of a section of an arc of longitude.

Inscribed in the photograph are all these layers of history, of measurement of time and space. In Raqs’ re-animation of it, we see the corrections of more time and political history. Corrections and recorrections, in multiple dimensions. The work itself inhabits what seems to be a strange new space, somewhere between photography and video, a liminal, critical space of memory.

(Remember when Flickr introduced video? Remember the ‘long photo’. Think of the Lytro camera, but for time, instead of space.)

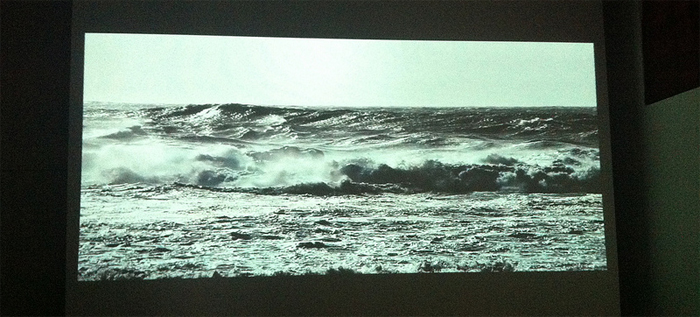

In May, in Portugal, I saw FrameArt, a travelling exhibition of European video art. Mario Garcia Torres’ A Brief History of Jimmie Johnson’s Legacy, which played delightful games with time and memory, inserting black and white stills from films—Steve Martin rollerskating around LACMA in LA Story; Ferris, Cameron and Sloane forming strange figures in the Art Institute of Chicago—into the history of performance art. Alberto Plácido’s Tempo, on the other hand, de-animated the energy of the ocean, epic slow-motion and distended noise of waves crashing onto a beach.

At Parasol unit, a show by Belgian photographer and video artist David Claerbout. There is much playing with time. In the first room, in the pitch black, the viewer comes face to face with an entire auditorium. Just lit enough, you see the conductor of an orchestra and the large audience staring back at you—so subtle and gilded that you are convinced a subtle animation is at work. You start to see it everywhere, convinced it must be present, in the mist on the window-glass of Breathing Birds. (At the Swedenborg Society last year, Iain Sinclair and Brion Catling uncovered a similar picture: an audience looking back at the painter. In turn, Catling snapped photographs of the then-audience with a disposable camera; opened the camera, and ate the film.)

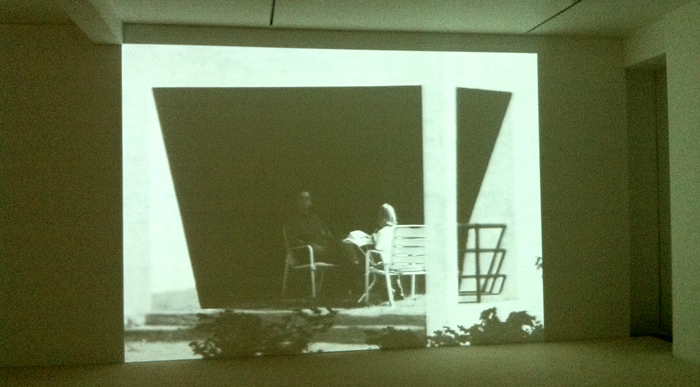

But it is Untitled (Carl and Julie) that completes the interaction, the study. A young girl and her father sit at an outside table, half shaded from the sun. A light beam trips as the viewer enters the room, and the father tips his chin, the little girl turns her head for a moment, to scrutinise the viewer, before turning back to her homework, relaxing back into the frozen moment, the photograph, only momentarily disturbed.

(Another work in David Claerbout’s show: Bordeaux Piece. A 14 hour film, composed of a single, cinematic scene filmed every 10 minutes over the course of a single day, repeated over and over again until the drama disappears, and the day’s natural light, shifting each time to represent the passage of time itself, becomes the central actor. Bordeaux Piece is back-projected onto an opaque screen from the next room, so that the projector itself forms a second sun, shining through the work.)

I am reminded of these things: of Jack’s description of the map as an animation on pause; of déjà vu and presque vu and the physiological slippages of time and memory; of Loopcam and Cinemagram and technologists putting the tools of artists, drawn from art and consideration, into the hands of users as toys; of the animated gif (obviously), a historical accident in itself, born of compression; of quantum tunnelling, by which we create memories in flash hard drives in ignorance of classical physics; of anamnesis; of planes that intersect in more dimensions than we think we inhabit or can visualise. Self-correction. Liminal moments, moments of ritual and disorientation, where we accept that we cannot understand. The moment may be infinite.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.