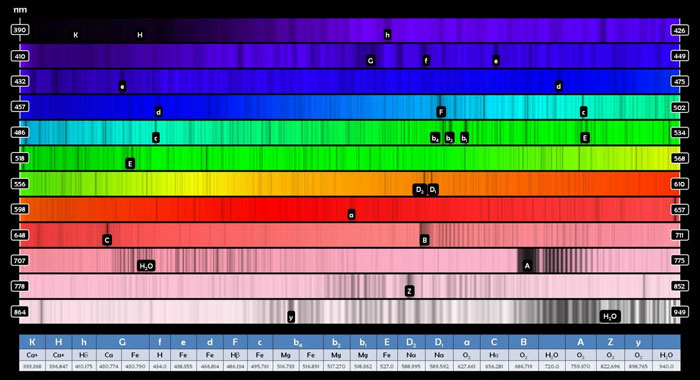

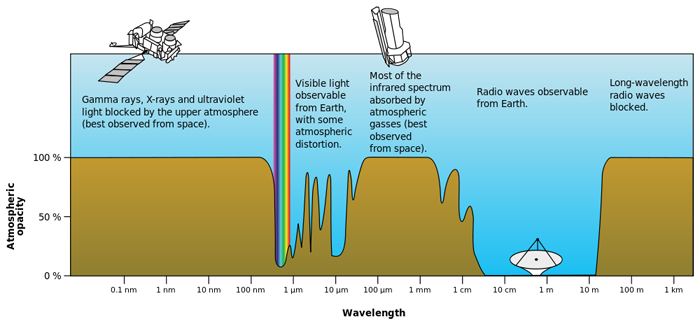

I first heard about the Fraunhofer Lines from Jamon Van Den Hoek, a remote sensing specialist, formerly of NASA and now at Oregon State, whose work on conflict ecology has inspired me for some time. In a presentation at Goldsmith’s last year, Van Den Hoek showed an extraordinary image: the full spectrum of the sun’s light, as it’s available to us on Earth. It’s full of gaps, dark patches, where frequencies have been occluded by the particles and interactions in the Earth’s atmosphere, in space, even in chemical reactions inside the Sun itself. Van Den Hoek’s point: you have to know the scope and limits of the material you’re working with; in this case, the shape of light itself.

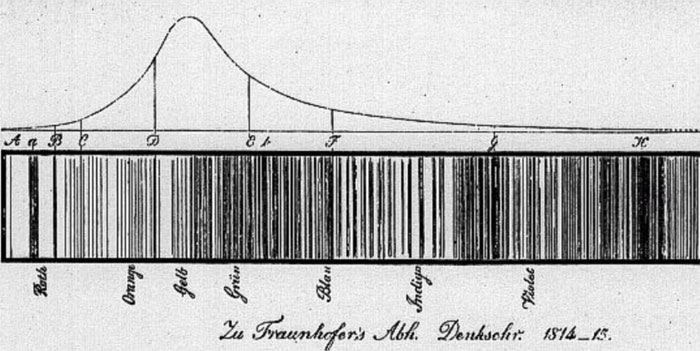

These gaps are called “spectral lines”, and they were discovered by German optician Joseph von Fraunhofer in 1814, although they had been noticed by the English chemist William Hyde Wollaston in the previous decade. In order to test various glasses he produced with machines and furnaces of his own devising, Fraunhofer developed what is today known as the spectroscope, an instrument for analysing parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Splitting the sun’s beam through a prism, he found that its light contained some 574 fixed, dark lines, which are today known as Fraunhofer Lines – and, as optical technologies have improved, millions more of them have been discovered.

I have been fascinated with the politics of light for some time: how it is cast, how it is seen, and who sees it, in what frequencies and spectra. The Light of God and the Rainbow Plane are illustrations of a privileged form of vision, the ability to see through other spectra, a wider field of vision, encompassing not just space, but frequencies, invisible to the unaugmented human eye. Activities carried out in this domain should be subject to the same scrutiny as in the visible spectrum.

*

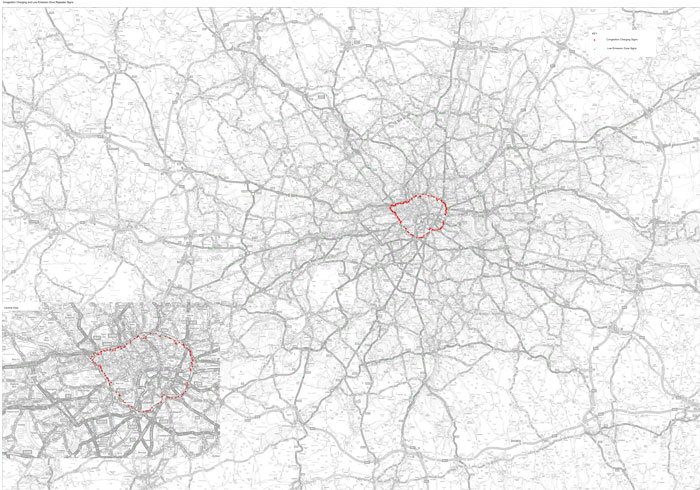

For several years I have been using Freedom of Information requests as one of my primary tools of investigation. In the UK, there is a legal right to request information from government bodies, and using this mechanism I have asked questions about land ownership and access in the City of London, the costs and operation of surveillance cameras, and the use of drones by the police services, among many others. One persistent subject of interest has been the use by London’s Metropolitan Police of vehicle data gathered by Transport for London, the capital’s transit authority.

I’ve written extensively about ANPR elsewhere, so here’s the short version: for more than a decade now, traffic moving around London has been monitored by thousands of cameras, which can identify individual vehicles by their license plates. First there was the Congestion Charge Zone, then the Low Emission Zone, and now hundreds more route monitoring cameras. Firstly, it took months just to discover the approximate number of these cameras, and their locations, from the relevant authorities, and then many more months to discover that, in contravention of numerous guarantees given to the public, all the data they gather is handed directly to the Police, who can use it in any way they see fit. It’s a vast surveillance network, possibly one of the most pervasive in the world, and the authorities don’t like to talk about it very much.

The first thing I learned in pursuing these questions is that these responses are rarely very useful. Freedom of Information is broken, and I have yet to learn anything by it which I did not subsequently confirm from information already in the public domain, obtain directly from press departments, or pursue all the way through an internal inquiry to an appeal to the Information Commissioner.

The other thing I learned is that it’s a useful tactic to ask the same question twice, to both ends of the discussion. So if you’re interested in correspondence between, or joint reports by, two organisations, then you fire off separate requests to both parties, and see what comes back. What is interesting is the shape of the refusal.

Fraunhofer’s spectral lines are absorption lines; that is, they are caused by the absorption of photons on their journey from the transmitter – in this case, the Sun – to the receiver. The same principle can applied in reverse, to measure the reflectivity of the Earth’s surface, and tell us where vegetation is healthy, or where the earth is dry. As photons travel through space, they encounter numerous obstacles. Different elements along the way absorb and re-emit photons at different frequencies. Each element has a fixed set of absorption frequencies: Oxygen at 898.765, 822.696, 759.370, 686.719, 627.661 nm; Helium at 587.5618 nm, and so on. By splitting the light, and looking for the dark spots, we can see into the reactions which have produced the light in the first place, and the forces which have shaped it on its way to us. Something of the same is true of information as well, because information is just another signal, propagated from transmitter to receiver, and subject to all kinds of interference along the way.

*

Most of the documents I receive from Freedom of Information requests are redacted in some way; that is, certain sections, certain frequencies, from individual words to whole pages of text, have been removed, blacked out, censored. Obviously these are the most interesting parts. Here, for example, are three pages from the Metropolitan Police’s Fifth Annual Report to the Information Commissioner on the Operation of the Data Protection Certificate relating to ANPR Data. All of the information remaining is already in the public domain; everything else has been redacted. No light gets through.

Obtaining two copies of these documents however – a second set from the Home office – is more interesting. The patterns and the style are different. Behind the redactions is evidence of a human hand, an intentionality.

I wrote software to explore these redactions, to map and fingerprint them, in these and other documents. Here, for example, is every redaction in the US Senate’s Intelligence Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program (under redaction, all information regimes begin to look alike):

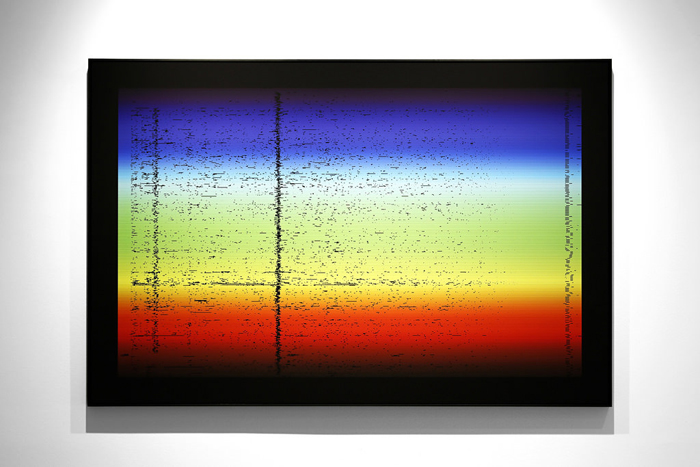

I wrote further software to map the position of these redactions, turning three-dimensional pages into data points, pinning down the occlusions and evasions, even as they floated in meaningless space. Split the beam through a prism, look for the dark spaces. Like the images which make up Dronestagram, attempting to stand in for the absent craters and piles of rubble, the meaning is in the omission. A spectroscope for information ends up recreating the Fraunhofer Lines:

This is that same report, the one about torture, rendered as a spectrum, one line per page. Its signature pattern is the cluster of lines which run down the right hand side; that’s the footnotes, where all the real information resides, heavily redacted.

Likewise, the middle image below is a close analysis of the ones to either side of it, two sets of documents from TfL and the Met compared, the subtle differences between each release providing the few clues we have to how this information has been massaged, refracted, diffused and redirected.

These images were created for The Glomar Response, an exhibition at Nome in Berlin which, in various works, addressed the relationship between government and citizens through their relative levels of access to information, their ability to see with the full spectrum available to them. Inevitably, it also dealt with the limits of such vision.

This tension – between the ability of governments to use technological and legal structures to obscure information, and the ability of engaged citizens and interested observers to read that information using almost exactly the same tools – is perhaps even more evident in a series of Fraunhofer Lines produced for the exhibition Art In The Age Of… Asymmetrical Warfare at the Witte de With Contemporary Art Institute in Rotterdam. These three realisations are based upon redacted documents released under Freedom of Information legislation by the Dutch government’s investigation into the crash of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17, which was shot down over the Ukraine in July 2014.

As with other such episodes, little new was understood from this “release” of information. Meanwhile, citizen investigative journalists collaborated online to find, share, analyse, and geolocate information about the crash, the speed and transparency of their approach in sharp contrast to the reluctant and occluded official response.

Transparency, of course, is not the same as objectivity or truth, and it is precisely into that fissure that The Glomar Response delved. The Glomar Explorer was a ship built in the 1970s by the CIA to raise a lost Soviet submarine. The discovery and publicising of this covert mission led to the formulation of the now stock official response: “we can neither confirm nor deny”. It was the regular appearance of this phrase, coined to protect the darkest secrets of the Cold War, in correspondence with my local council, which led me, first to despair, and latterly to a new appreciation of the relationship between information and power.

Joseph von Fraunhofer played the sun’s light through a prism, and saw the elements of the universe in the form of spectral lines. Now, we see power in the absences where there should be information, in the sure knowledge that something always exists in the lacunae of official narratives, in the shadows of oft-told stories. New tools are every time a new way of seeing and representing the world around us; what we choose to reflect upon is the challenge they hold up to us.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.