In March I was asked by Claire Warnier and Dries Verbruggen of Unfold to contribute to the exhibition After The Bit Rush at Mu, a multi-disciplinary gallery in Eindhoven, the Netherlands. My contribution: For Our Times, 50 Pirate Works, has been on show there since 22nd October, and will be for another week, when the exhibition moves to Artlab Deventer.

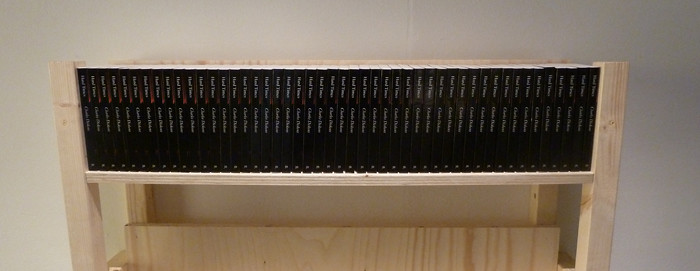

The work is based on Charles Dickens’ novel Hard Times, originally subtitled For These Times. It consists of 50 identical-looking paperback books, where every text is different. The transformations are stylistic, algorithmic, and literary.

Some copies appear with distorted and pixelated text, or with pages missing or transposed. Some copies have been robo-translated into other languages: I cannot speak to their accuracy. One copy has been translated into another language and back into English, to produce word salad (Yes, there is a lolcat version). In some the words have been changed: a building enlarged here, a dress changes colour, a character lives or dies. Sometimes, whole chapters have been rewritten to alter the outcome, or move the action to another town, another country. Sometimes a word, sometimes more. Each one different.

If that sounds familiar, it is of course the logical conclusion of The Author of Everything.

I wrote that story having visited India, and thinking about the new house of wisdom. And then Andrea Francke of the Piracy Project showed me her copies of books from Peru, where local copies appear on the market before the “official” international editions, and pirates rewrite popular novels to their own tastes. Of course, it is happening already.

True “publishing” is now within the reach of everyone, from international conglomerates to independents, from pirates to private individuals. The book is no longer a sacrosanct object: it is subject to the whims of any reader who wishes to change it for themselves. Engagement with culture has fully switched from active author and passive reader to a shared creation of the text, where every interaction is a recreation and reimagining. (In fact, this has always been the case; as ever, technology mostly reveals what has been hidden in human affairs, rather than prompting entirely new behaviours.)

Hard Times is a satire on the Utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham and James Mill, who held that a totally rationalised society would result in the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Dickens, who based Coketown, the fictional locale of Hard Times, on the mills of Manchester and Preston, believed that this rationalisation, the rationalisation of Thomas Gradgrind, who believed in Facts over Fancy, would result in greater misery, more work and less imagination. Hard Times is always For These Times.

After The Bit Rush is concerned with Post-Digital Design, the notion that “whether something is analogue or digital does not matter anymore. Everything we do is influenced by digital technology. Just as air and water, the property of being digital is only noticed when it is not there, not when it is there.”

For Our Times is the least apparently digital work in the exhibition; it bears no marks that set it aside from traditionally produced books, nothing to show that it is not what it presumes to be. Only by comparing each edition, sometimes at a word-by-word level, are the differences apparent. I’m sure many visitors are not even aware that the bare shelf of books is even part of the exhibition. My favourite thing: several copies have already been stolen from the gallery. They will inevitably re-enter the food chain at some point, becoming someone’s Hard Times.

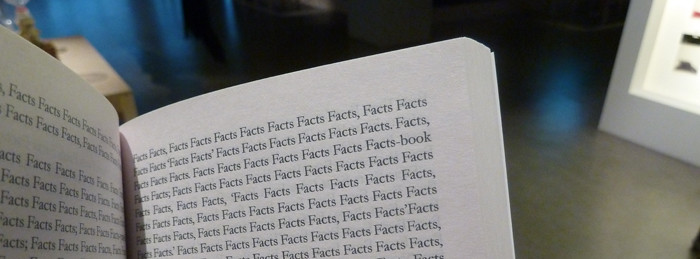

And that’s OK: one of the things I learned in attempting to produce 50 interesting variants on the text is that it is very, very hard. Whatever is done to the text, it is virtually impossible to extinguish Dickens’ intention without extinguishing the whole work (as in the case of the copies which read simply “Fancy fancy fancy fancy…” or “Facts facts facts…” for 300-odd pages). The text stands; it is greater than paper.

I’m very grateful to Angelique Spaninks at Mu, and to Claire and Dries, for letting me try this one out.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.