There’s been a bit of a fuss recently when it was reported that an Indian engineering student had developed a new technique for data storage which not only massively outperformed the most modern competing techniques, such as DVDs, but did so using the far more ancient medium of paper.

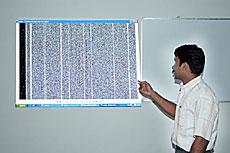

Sainul Abideen’s “Rainbow Technology” uses multicoloured geometric shapes to store data on a printed page. This data can then be read back into a computer using a simple optical scanner. The original article claimed that text typed on 432 pages of foolscap paper could be stored on a four square inch sheet in rainbow format. The writer also watched a 45-second film which had been stored on an ordinary sheet of paper. Such a concept seems to invert the usual flow of such technology: away from the visual and tangible; toward the virtual and inscrutable.

Sainul Abideen’s “Rainbow Technology” uses multicoloured geometric shapes to store data on a printed page. This data can then be read back into a computer using a simple optical scanner. The original article claimed that text typed on 432 pages of foolscap paper could be stored on a four square inch sheet in rainbow format. The writer also watched a 45-second film which had been stored on an ordinary sheet of paper. Such a concept seems to invert the usual flow of such technology: away from the visual and tangible; toward the virtual and inscrutable.

There have been a number of counter-claims since the original article was published – the touted 90 to 450GB capacity of a single ‘disc’ or sheet has been widely debunked – but the potential is fascinating. Firstly, even a 100MB sheet (a more realistic figure suggested by the debunkers) would provide simple, recyclable storage which uses none of the hard-to-dispose plastics, metals and toxins common in contemporary storage devices. Secondly, the cost of distribution drops massively.

100MB is more than enough to store hundreds of full-length novels. An entire library could be printed on a sheet of paper, posted by regular mail, and scanned by the recipient. The week’s news would fit on the postage stamp. The technology inhabits a strange hinterland: paper-based, requiring the intervention of a computer to be read, like old mainframe punched cards.

CDs and DVDs are not reliable storage mediums: vast tracts of human knowledge are now maintained only by constant rereading and re-encoding. We have not yet developed a medium to rival the book – nothing now in use could be relied upon for anything like a thousand years: the world’s oldest book is some way past this. Might we need to resort to printing our data onto physical sheets?

Such minglings of low- and hi-tech, of contemporary and ancient technologies bring to mind projects such as the Long Now Foundation’s Millennium Clock, which seeks to design a clock that will run for a thousand years, or the strange artefacts proposed for Yucca Mountain in Nevada to communicate with unknown visitors in an unknowable future.

Perhaps we should be working not only on new books, but on new languages: languages with 64, or 128 letters; languages which condense more information smaller signals. Computer languages have built-in error-checking and correcting protocols to prevent errors of communication. Perhaps we need to learn the language of computers, in order to communicate better with one another.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.