Earlier this year, I spent a couple of weeks in Oslo, as part of the After Belonging In Residence programme, part of the Oslo Architecture Triennale 2016. The triennale opens today, and the result of my residency is installed at the National Architecture Museum.

Each of the In Residence reporters was given a site to respond to; mine was Oslo’s Gardermoen Airport. I spent many happy and curious hours exploring the terminals, watching the herculean snow management operations, and talking to baggage handlers, fire crews, security guards, cafe staff, and travellers.

One of the most interesting places I was kindly given access to was the Airport Operations Center. I’m sorry to say that I am not allowed to share photographs of it, but it is exactly as mundane-Bond Villain as you would imagine, with huge flat-panel screens showing everything from wind direction and temperature out on the airfield to hundreds of CCTV feeds, baggage carousel statuses, passenger flow times, and all manner of other alerts. Into this one room flows every available piece of information about the ground status of the airport. Everything above the ground is the domain of the control tower, the only place allowed to override the orders of the Operations Center – because, as one operator told me, “they’re closest to God – them and the Air France pilots.”

The other place in the airport that might be closer to God is the meditation centre, or Stille Rom (above). I’ve written before about these fascinating spaces, which seek to create a zone of quiet, stillness and reflection within the highly networked, busy and omnidirectional space of the airport. You can read my essay on these spaces, which discusses Gardermoen as well as a number of other airports, at the Witte de With Review website (or download it here if on mobile).

That essay dwells on one recurring feature of the multifaith space: the inclusion of a qibla, the arrow which points the faithful in the direction of Mecca. The qibla appears in many forms in different places. At London’s Heathrow, it’s a metal stud screwed to the floor; at Stansted a laminated card pinned to the wall, in Athens, a beautiful beam of light. (For a taste of these spaces, see this collection of photos I’ve taken over the years.)

Oslo’s meditation room contains no such direction – but, as I note in my essay, this is less necessary now that the qibla and tools like it are available to anyone with a smartphone, in the form of a downloadable app, which uses the phone’s in-built compass to determine the direction of prayer. Nevertheless, as I found at Gardermoen and elsewhere, those praying often leave a trace on the floor or skirting board for others who may not have the same kinds of access. (Biro marks at at Gardermoen, above).

This reliance on networks consisting of both smartphones and more traditional forms of communication mirrored my experience of the refugee crisis in Athens and the Greek islands. The camps on Lesbos, the squares of Athens, and all ports in between, are thronged with SIM card vendors, offering cheap data packages. On the ferries, those in transit share information about which border points are open, which countries are (relatively) friendly, where to buy bus tickets – information often passed back from those who have already gone ahead, via Whatsapp messages and Facebook groups. Such information is not always reliable, but forms a vital part of any journey, and mirrors once again the systems of calibration, control, and flow engineered in the contemporary airport space.

For the Architecture Triennale’s exhibition at the National Museum of Architecture in Oslo, I have installed a work called Wayfinding, consisting of a constantly-updated information screen and floor projection. The modern usage of the term “wayfinding” dates from Kevin Lynch’s classic work of architectural theory The Image of the City, published in 1960, and defined there as “a consistent use and organization of definite sensory cues from the external environment.” The term dates further back, encompassing techniques such as Polynesian open-water navigation, and is most often used today to denote the highly organised signage developed for airports and other busy public spaces. Its most vocal contemporary proponent is the Danish designer Per Mollerup, who created the signage systems for Gardermoen as well as many other international airports and rail termini.

That original definition from Lynch still stands, but can be expanded. The airport is a prime example of one of Rob Kitchin and Martin Dodge’s Code/Space(s), a concept I have long been fascinated with, which examines the interplay and interdependence between software and architecture. As everything, ourselves included, becomes networked, so the boundary between Lynch’s “external environment” and our own sensorium starts to blur and break down. Wayfinding is not a stop-start process of moving from one point to another, but a constant flow of data from multiple sources, subtly inflecting our passage through the world. Every bit a trimtab.

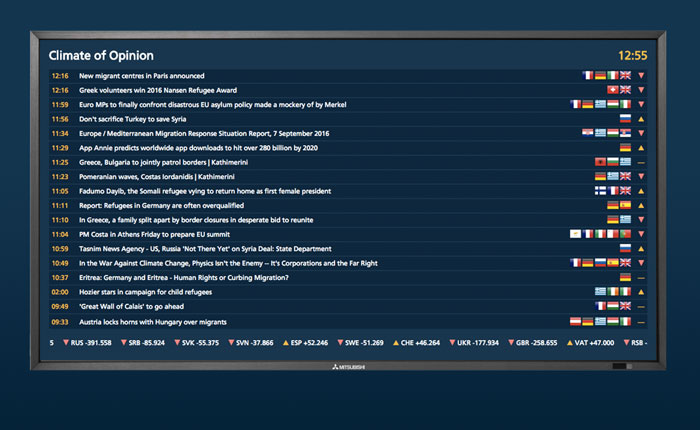

Wayfinding, the installation, takes as its source material news stories published online about migrants and refugees. It reads hundreds of these every hour, as they are published, and analyses them for location and sentiment. Location means the place or places that the story is about; sentiment means the tone of the article – is it positive or negative, and to what degree? (Sentiment analysis is an important and growing tool in newsgathering, analytics, and investment, and seems important to understand, whether its companies analysing social media for product research or political views or automated stock trading based on online chatter.)

This information is aggregated and displayed as a real-time screen of recent news stories, together with their tone and location. Behind the screen, each story is mapped and weighted, so that an ever-changing sentiment map of Europe is created; a model of the shifting climate of opinion towards refugees and migrants across the continent.

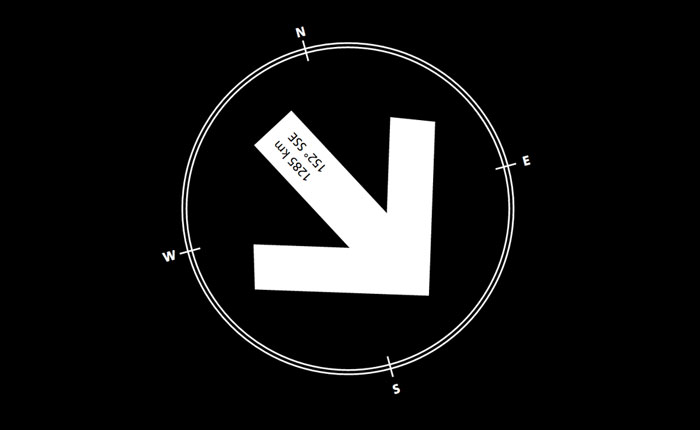

The “pole of inaccessibility” is defined as a point on the Earth’s surface which is harder to reach by some metric; the Northen pole of inaccessibility, for example, is a point on the Arctic pack ice calculated to be furthest from any solid landmass. Wayfinding, by contrast, calculates a pole of possibility: the point in Europe currently reported to be expressing the best (or least worst) sentiments towards refugees and migrants.

Onto the floor of the National Museum is projected a compass rose, the arrow of which points, constantly, towards this pole.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.