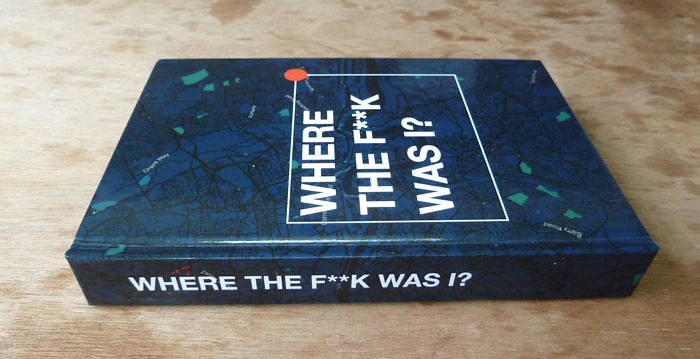

I have made another book from data; a printing-out of databases. This one is called Where the F**k Was I? and consists of 202 maps based on my movements over the past year.

I say “based on” because the data was not recorded by me, but by my phone. In April, researchers Alasdair Allen and Pete Warden revealed that the iPhone was storing location data without the users’ knowledge. Using their instructions and my own scripts I extracted 35,801 latlong pairs stored on my phone between April and the previous June (when my phone was last updated, wiping its memory). These are plotted on OpenStreetMap, one map for each day, together with a brief note where I wanted to tie it to a real event.

You can purchase an edition of the book on Lulu. There are more photos on Flickr.

I think: This digital memory is better than mine—it frequently recalls things and places I have no personal, onboard memory of, and over time I come to rely on it over my own memories, just as I recall my sister’s birth not through my own vision, but in the form of a photograph of the event. I appear, physically and impossibly, in my own mental image.

Francesco Pedraglio, who I saw perform at the National Portrait Gallery last week, spoke of “non-experiential memories”. He meant things which had not happened, but of which we have memories nonetheless. He meant delusions. (In the same evening, Tom McCarthy said “Realism is a literary style with no more purchase on the real than Burroughs or Gysin”.)

This digital memory sits somewhere between experience and non-experience; it is also an approximation; it is also a lie. These location records do not show where I was, but an approximation based on the device’s own idea of place, its own way of seeing. They cross-reference me with digital infrastructure, with cell towers and wireless networks, with points created by others in its database. Where I correlate location with physical landmarks, friends and personal experiences, the algorithms latch onto invisible, virtual spaces, and the extant memories of strangers.

(Other aspects of the device’s place-making I enjoy: I love its hunger for new places, the inquisitive sensor blooming in new areas of the city, the way it stripes the streets of Sydney and Udaipur; new to me, new to the machine. It is opening its eyes and looking around, walking the streets beside me with the same surprise.)

Or how about this: In The City & The City, China Miéville describes two cross-hatched urbanities, two cities occupying the same space and time, whose citizens have been acculturated from birth to see and unsee, their eyes settling on the streets, buildings and people of their own city, and sliding sightlessly over the structure and inhabitants of the other. To transgress this perceptual boundary is to both enact and provoke Breach—an illegal act, and also the name of the strange, supranatural entity that enforces the separation.

We share the city, and increasingly the world, with another nature, invoked by us but long since split at the root, which looks at the same world with other eyes. The other city is the abstract machine: the digital networks, access points, substations and relay points, datacenters and fiber rings; its inhabitants are sensors and screens. Seeing through the machines’ eyes is a kind of breach: accessing a grosstoplogy of the network. (Timo Arnall breaches, oh so elegantly, here and here.)

This is an atlas, then, made by that other nature, seen through other eyes. But those eyes have been following me, unseen and without permission, and thus I consider provoking breach a necessary act.

Perhaps how Kevin put it, in a recent talk, reappropriated for the robots: “These are the astronauts for Earth, and they’re inventing new ways to see rather than things to look at. And rather than inventing new places to go, they’re inventing new ways to travel.”

Or this: At the Worlds literature festival this week in Norwich, the Sri Lankan-Canadian writer Shyam Selvadurai spoke of the space between his identities represented by that hyphen. A place where “the tectonic plates of cultures rub against one another, producing the eruption of my work.” (I like that, that the challenge is not just to write at or about the interstices, but about what is forced up by the pressures between them.)

Where Selvadurai is interested in the space between two human cultural identities, I suppose I am interested in the space where human and artificial cultures overlap. (“Artificial” is wrong; feels—what? Prejudiced? Colonial? Anthropocentric? Carboncentric?)

There are no digital natives but the devices themselves; no digital immigrants but the devices too. They are a diaspora, tentatively reaching out into the world to understand it and themselves, and across the network to find and touch one another. This mapping is a byproduct, part of the process by which any of us, separate and indistinct so long, find a place in the world.

Or: I made a book. You can buy it if you like.

[…] latest is Where the F**k Was I?, a beautiful looking book of 202 maps based on his iPhone tracked movements over the past year. In […]

Pingback by Trackers | @sizemore — June 24, 2011 @ 5:58 pm

[…] book is documented on his site and on flickr. blog comments powered by Disqus […]

Pingback by dataists » Snippet: Where the F**k Was I? — June 24, 2011 @ 7:48 pm