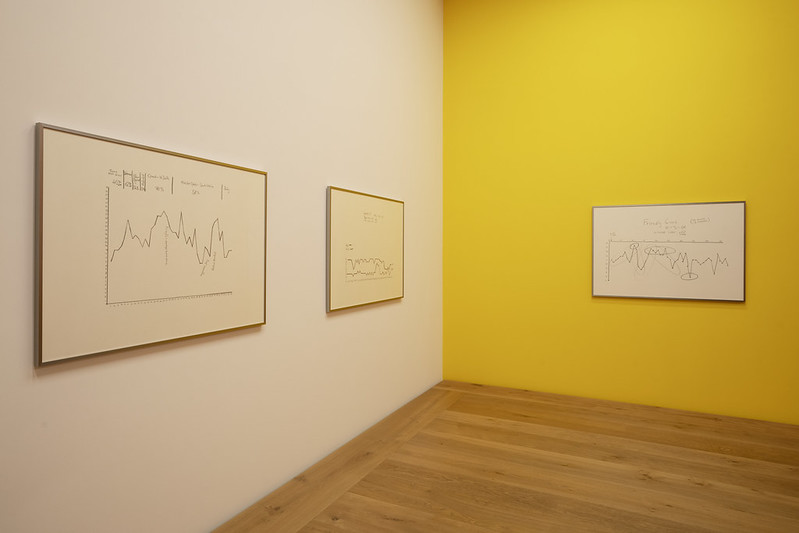

An installation at Kunthaus Zurich on the theme of media history, education, and the technology of attention.

Some time ago, I was commissioned to write an essay about children’s media and the capture of attention by the Centre for Media, Technology and Democracy at McGill University. You can read that essay in full, but here’s an excerpt, which concerns the research done by the Children’s Television Workshop (CTW) in the 1960s, which led into the development of Sesame Street:

One of the workshop’s key innovations was a device Palmer termed “the distractor”. Initially on visits to “poor children in day-care centres” and later in specially designed observation laboratories, Palmer and his colleagues would set up a television showing Sesame Street episodes, and next to it they would set up a slide projector, which would show a new colour image every seven and a half seconds. “We had the most varied set of slides we could imagine,” said Palmer. “We would have a body riding down the street with his arms out, a picture of a tall building, a leaf floating through ripples of water, a rainbow, a picture taken through a microscope, an Escher drawing. Anything to be novel, that was the idea.” Observers would sit at the side of the room and watch a group of children as the episodes played, noting what held their attention and what didn’t every six and a half seconds for up to an hour at a time.

Individual characters, short skits, and even whole episodes lived or died by the distractor. By the time they got to broadcast, the show’s attention rating averaged around 85 to 90 percent, and some reached 100 percent, as the crew learned to trust the distractor and absorbed its lessons. For Palmer, the distractor enabled the team to hone Sesame Street into a finely tuned educational instrument: “After the third or fourth season, I’d say it was rare that we ever had a segment below eighty five percent. We would almost never see something in the fifty to sixty percent range, and if we did, we’d fix it. You know Darwin’s terms about the survival of the fittest? We had a mechanism to identify the fittest and decide what should survive.”

I’ve been fascinated by the Distractor ever since I first read about it. It seemed to embody so many things I was fascinated by, from visual attention, to the use of technology to capture and hold attention, to the origins of children’s screen-based media and what’s happened to it, and even randomness.

I find the device particularly mesmerising because I don’t know how I feel about it. The research performed by CTW in the 1960s and 70s laid the groundwork for screen-based educational programming worldwide, and Sesame Street made a positive difference to the lives of millions of children, especially for many from disadvantaged backgrounds. At the same time, it marks a moment in which technological solutions were chosen over social ones, and education was outsourced to screens and corporations. Today, techniques developed by educationalists in the 1960s are deployed in automated systems, such as mobile apps and social media, and make possible the global ‘attention economy’, under which human attention is treated as a resource to be captured and exploited.

This fascination has caused me to spend a not inconsiderable amount of time tracking down references, descriptions, and actual data on the Distractor, its use and results, from the Children’s Television Workshop archives in the Mass Media & Culture collection at the University of Maryland (thanks to Michael Henry, Laura Schnitker, and James Baxter at UoM for their invaluable and generous assistance). Initially, I was just interested in reconstructing the contents of the slideshow, but when I was offered a commission by Kunsthaus Zurich last year to develop a new work for their digital programme, I decided to restage the mechanism in its entirety.

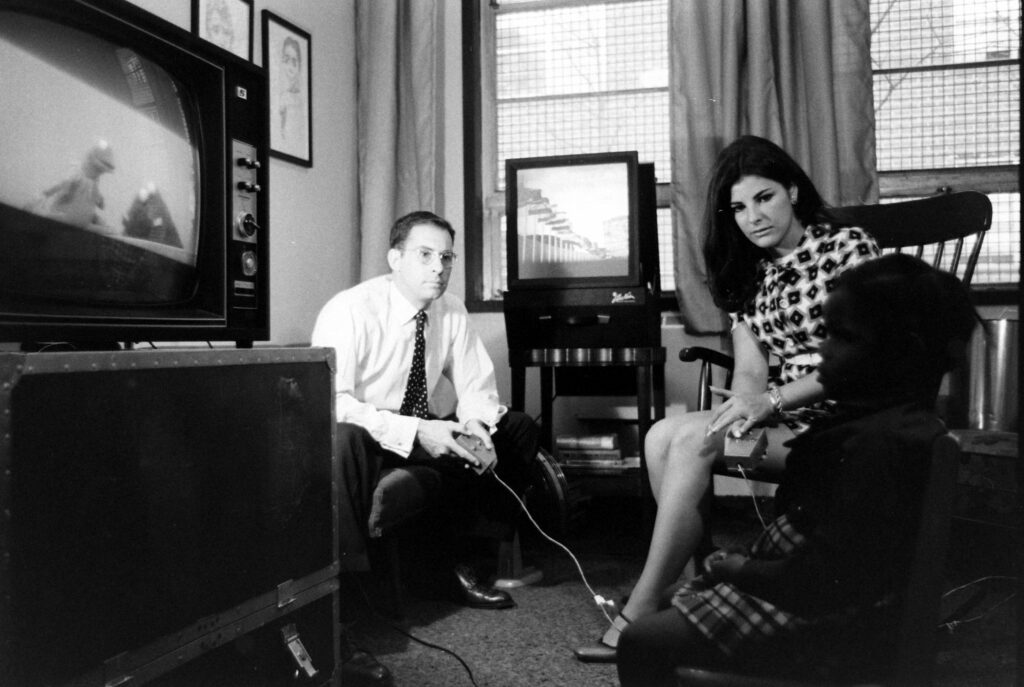

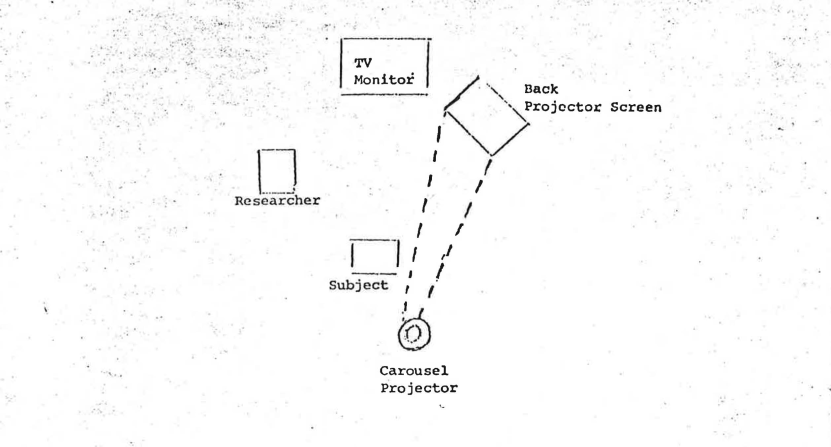

The above is the only photographic image I’ve found of the Distractor in operation, and I’m not sure it’s representative of most set-ups, although it’s certainly evocative, with the white researchers staring down at a black child, fingers poised on their electronic devices, while Kermit appears on one screen, and some kind of modernist architecture pops up on the other. The CTW archives contain a number of reports on the Distractor, including one entitled “The Sesame Street Distractor Method for Measuring Visual Attention”, published by Leona Schauble of Sesame Street Research in July 1976, and containing the following diagram:

For the Kunsthaus Zurich installation – which opened in May and is on view until Spring 2024 – I used this layout, sourcing period furniture and television equipment from Swiss second-hand sites (the installation does include a contemporary Parker Jotter – although only an expert would spot the differences between it and the model first introduced in 1954). The television shows the first ever broadcast episode of Sesame Street, from 1969, while the carousel slideshow, set to advance every seven seconds, contains ninety or so randomly-selected images from collections of vintage slides purchased on ebay and elsewhere.

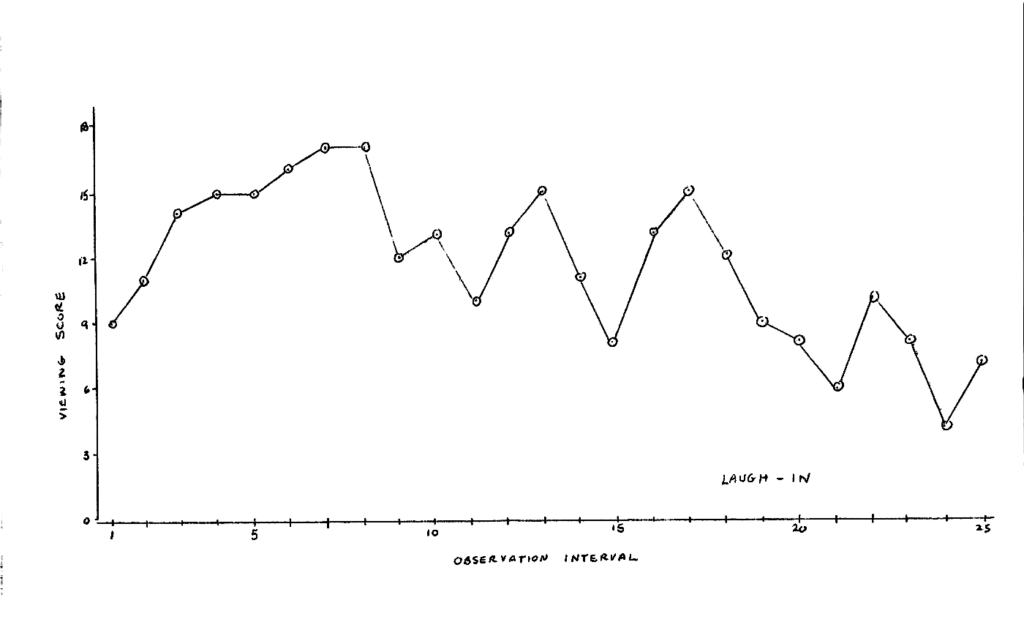

Some of the most fascinating artefacts in the CTW archives were the original “Distractographs”: hand-drawn analyses of the results of the Distractor sessions, where researchers would plot the childrens’ attention over time, as they watched episodes of Sesame Street and other shows, while the Distractor attempted to do its work. For the installation, I reproduced half a dozen of these by hand to hang on the walls of the gallery:

(The wall colours, by the way, were chosen based on Pantone’s Sesame Street colour range.)

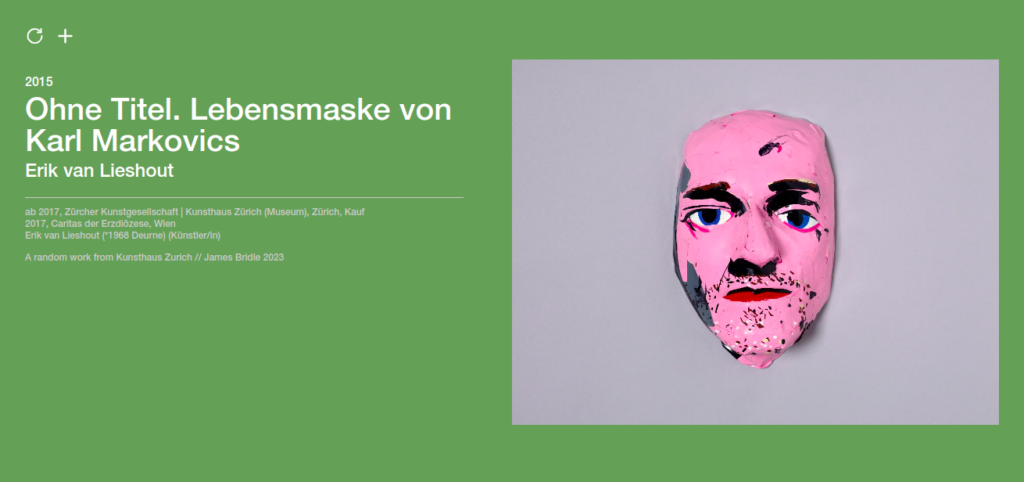

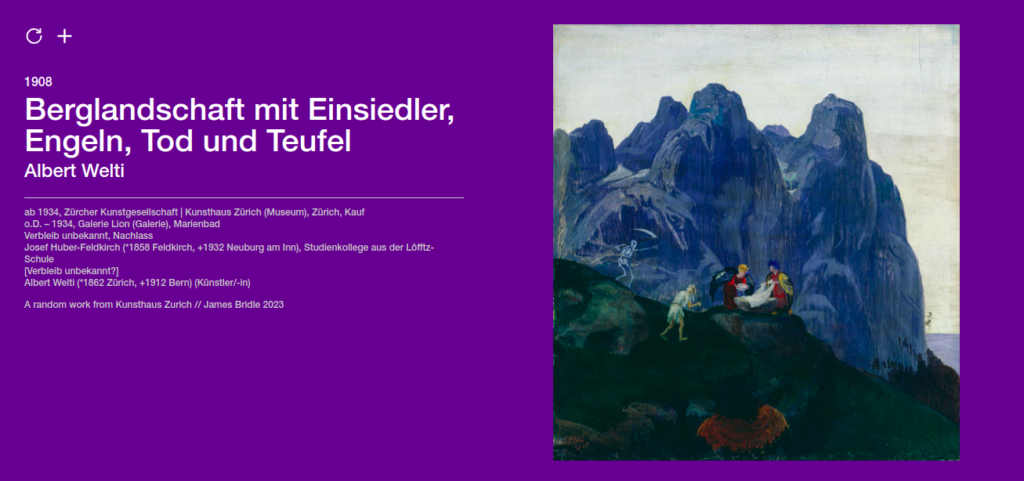

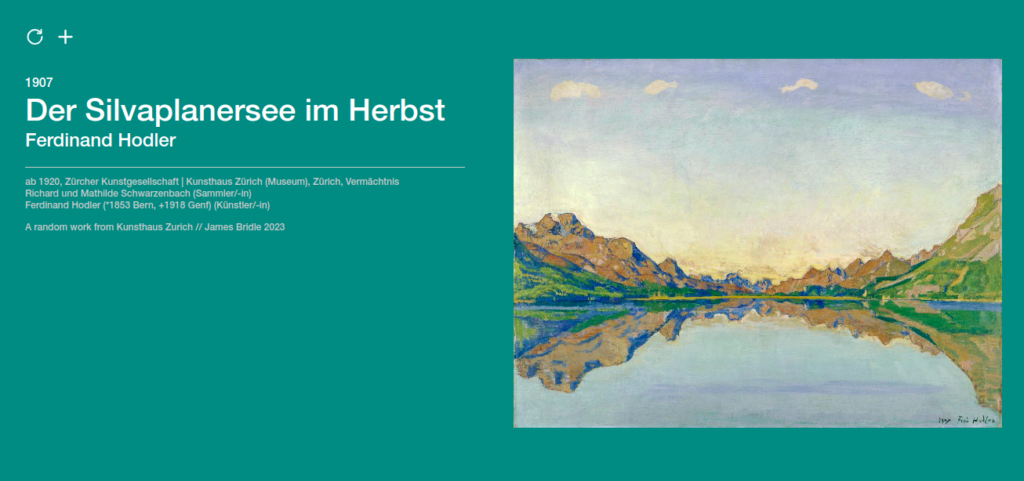

Finally, to accompany the installation, an online work continues the work of the Distractor into the present day. This work can be found at distractor.jamesbridle.com – visiting this page will present you with a random work from the Kunsthaus’ collection, together with information about its title, creator, and provenance. You can set this webpage to be the default new window or tab page in your browser settings, in order to constantly distract yourself with art (it’s quite nice, I promise).

Huge thanks to curator Mirjam Varadinis and to everyone at the Kunsthaus for their support in making this work happen. Particular thanks to Tony Kranz for his excellent and patient technical assistance throughout.

More information about the programme is available at digilab.kunsthaus.ch.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.