Recently returned from Mexico, and still too jetlagged to write up my experiences and talk at SXSW, I present instead some rambling recollections made up from my notes on Mexico City, where I walked a lot (in one very small area of the central city), went to bookshops, and, in one of those out-of-place experiences that suit some books so well, devoured WG Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn—but don’t blame either of us for what follows.

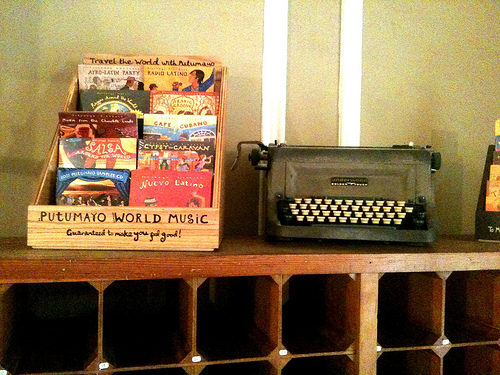

The book-buying started on the second day, and rapidly spiralled out of control.

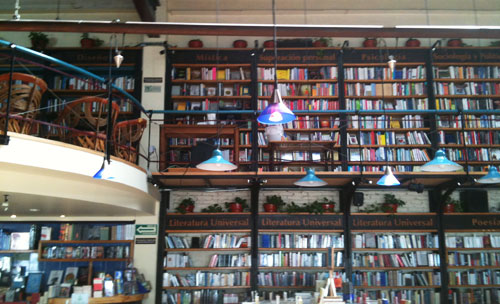

In the Péndulo bookstore in the Zona Rosa, less celebrated than the branch in Polanco, but nevertheless serene, caulked with climbing plants and where I breakfasted on Huevos Mexicanos and cafe con leche amid stacks of books sorted by publisher (Sexto Piso, Siglo XXI, AlmadÃa), I picked up Wallpaper Magazine’s guide to Mexico City: useless, somewhat irritating, but mercifully small, and totemic.

From Atrio, a bookshop and gallery on Orizaba, two bilingual monographs from Editorial Diamantina, Laureana Toldeo’s Paan and Pedro Reyes’ La Nuevas Terapias Grupales, and a blank notebook from Soloblock, inscribed simply and only: “Un 10% de la població mundial es zurda. Hay más zurdos varones que mujeres, sin que se sepa por qué” which I discover later means “10% of the population of the world is left-handed, more women than men, although we don’t know why”, and explains why the title is on the ‘back’ and the barcode on the ‘front’: the book itself is left-handed.

From the LibrerÃa Pegaso in the Casa Lamm on Ãlvaro Obregón, a signed and numbered edition of Franco Maria Ricci’s Carrol, printed on local paper in Milan in 1976 and containing Dodgson’s collected letters—in French—and tipped-in photograph of Victorian adolescent girls. It should be noted, independently and without context, that the finest bookshops are those that give you your purchases in plain brown paper bags.

In MUCA Roma, the local offshoot of the City University’s Arts Museum, a cuban artist’s film plays out his telephoned conversations with the tourist hotels he is not allowed to visit, many of which I have visited, if not stayed in. As the receptionists list the natural and luxurious entertainments on offer to state-approved guests, photos of an American couple’s idyllic holiday in Trinidad & Tobago play out on a large screen. On the floor above, artists Liudmila & Nelson have spliced together photos of old and contemporary Havana, digitally inserting the advertising hoardings so conspicuously absent from the real city and which seem, here, to be a small price to pay for that freedom.

At Conejo Blanco, bar, restaurant and art bookstore on Amsterdam, the wide boulevard that circles the former hippodrome in Condesa, I agonise over beautiful editions of Herodotus and Lucian—in Spanish, natch—but leave instead with a gilded portfolio of photographs by Gabriel Orozco, an artist whose show at the Serpentine Gallery a couple of years ago affected me greatly, in the hope that the connection between these images and his checkerboard, graph-papered art will somehow inspire my own amateurish attempts to capture his (occasional) home city on my cameraphone.

At some point, I begin to feel that I am carrying entire Latin American forests home with me. Also, I am afflicted with a terrible need to stop and write things down, at almost every corner, slowing my passage through the city and impeding motion. I am locked in this ridiculous two-step, unable to travel more than half a block before sitting down and writing out more, papering over the last thirty feet, dripping more ink onto the street: this absurd project, this incomprehensible, incompletable urge, this terror of forgetting and compulsion to record.

This city feels solid—I can see why Jonathan feels the need to leave regularly and get out to the desert or the hills. It must be easy to be claustrophobic here, to feel that there is no escape from the city which simply extends in every direction immeasurably on all sides, the streets like cuttings scored into the earth, the endless blocks excavated like the monolithic churches of Lalibela.

Stumbling by accident into an open-air book market (this happens to me a lot) in the Parque Mexico, I find the pocket English-Spanish dictionary I have actually been looking for. Collins, 1994 and badly faded, but unlike guidebooks, dictionaries take a long time to lose their usefulness. The park is full of emo kids, who I had also been half-looking for earlier, in vain, along Insurgentes, their reputed hangout and powerbase in the ongoing war with Mexico’s goths. School is out.

Crossing Ãlvaro Obregón again on my way to a second-hand bookshop where I find, amid the dusty stacks, a wealth of Mexican cookery books in English, I am nearly run down by a taxicab, whose occupant, a hennaed drag queen in crop top and lurid, Winehouse eye make-up, yells at me. I love drag queens, the more crazy and foreign the better, and all I can do is grin and eventually she does too.

Later, drunk, in the gay bookstore on Hamburgo: Muchachos, photographer Miguel Chavez’s typology of Mexican queens and the myriad ways they are subverting the traditional cultural and religious hegemony of the nation (“Mexico is the Iran of Christianity”, Jonathan says). It is so thick, outsized and printed on such heavy stock that I am forced to abandon it, disguised as a gift, with my hosts upon my departure, for fear of losing everything to the overweight baggage allowance.

* * *

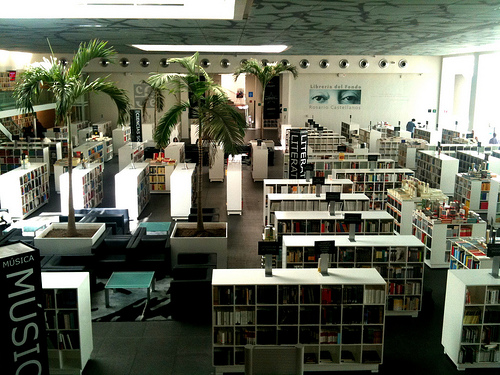

Anyone who comes to Mexico City expecting the frenetic, insane rush of its reputation will be surprised by Sunday morning. Walking through Roma and Condesa at 9am I have the quiet, cool streets almost entirely to myself. Down Aguascalientes and Gral. Bejamin Hill to the Bella Epoca, a former cinema transformed by the Fondo de Culturea Económica into a bookshop of IKEA modernist delight—clean, white, square shelving and palm trees and coffee tables. The FCE also publishes a range of books in translation, and I pick up Pieces of Shadow, a selection of poems by Jaime Sabines, translated by W.S. Merwin and bound in vivid green. Merwin wrote of Sabines’ poetry that what captured him was “the jarring authenticity of passion in the tone, a great cracked bell note of craving and frustration, irony and anger, outrage and black humour all jangled at once, unabashed, unsweetened, unappeased, and all of it essential to the rest.”

Sabines himself wrote: “Some day I want to sing of this immense poverty of our life, this nostalgia for things that are simple, this luxurious voyage upon which we have embarked toward tomorrow without having loved enough yesterday.”

In the Museo del Arte Moderno in the Bosque de Chapultepec, filled now with ambling families, a series of wonderful exhibitions. In the (surprisingly academic) notes on ‘Mexican Abstraction, 1950-79’, intense, vividly coloured, geometric and brightly suggestive, Kazuya Sakai is quoted: “La pintura no es sina condensación de ideas, pictoriaso filosóficos. Posiblemento pintar es, ante todor, pensa.” Francisco Moyao’s Artesujeto – Sujetoarte takes this to its logical conclusion: two simple, white, blank sheets of paper pressed with lines and dots, the artist actively creating a blank canvas, a space for the viewer, or the next artist, to think their own thoughts.

More exhibiton notes, this from ‘Hecho en Casa’, object-based production from the mid-80s to today: “Between 1923 and 1947 Kurt Schwitters worked on something that he called the ‘Merzbau’: a work that occupied all the space that contained it. It was made of large three-dimensional assemblages which involved different kinds of objects and materials. In it, the art object and the space around it were integrated into a single language or plastic project.”

Perhaps in the merzbau is to be found a useful analogue for Mexico City itself; its solidity, its integration with and essentialness to itself, its denial of a separation between the individual and the urban environment. Here, people pose for photographs in front of paintings as if they are landmarks or famous vistas on a long tour of foreign places.

‘Remedios Varo and Literature’, an exhibition of Varo’s painting curated with accompanying texts by the poet Alberto Blanco, quotes the 19th Century philosopher Paul Vitalis Troxler: “There’s no doubt there is another world, but that world is in this one, and to fulfill it completely it’s necessary to acknowledge it well and make a career from it.” Blanco notes that “Remedios Varo always understood that Art is something besides the artwork: the artifact. … [Varo] believed in knowledge which was capable of being encoded; not just into a piece of art, but into a piece made with art.”

After all that, the museum bookshop is a disappointment, evidently having forgotten the lessons of Fernando Gamboa, the founding curator of the Museum and subject of a small exhibition which strives to emphasise his commitment to the total integration of museology and the museum experience, even down to commissioning well-known illustrators to design the stationary with which he planned each exhibition. I leave with only a postcard, having intended to purchase at least three catalogues, which are non-existent. The postcard shows, in poor reproduction, Remedios Varo’s Creation of the Birds.

The Creation of the Birds is extraordinary: a figure, part-owl or dressed and masked as an owl with wide eyes and feathered limbs, sits at a table in a bare room. From the mouth of a miniature guitar, slung round its neck, whose opening sits above the heart, extends a cord or narrow tube, which runs to a pen, with which the figure draws or paints. The ink for this drawing is produced by an arrangement of flasks which appear to draw in moisture from outside via a funnel which extends through a small porthole, as well as from the atmosphere of the room itself, depositing red, green, and blue ink on an artist’s palette, alongside the sheet of parchment on the table. On the parchment, the figure’s pen draws multi-hued birds which, when the light of the moon is focused on them through a triangular magnifying glass, take flight and exit the room through the window.

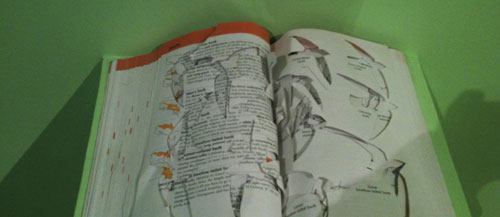

This transfiguration through light is seen too in Diego Rivera’s mural Man at the Crossroads in the Palacio de Bellas Artes, wherein the choice between peace and war, socialism and capitalism, is framed through two enormous lenses. (As Chris notes after our return to Europe from the Americas, “the light is different here”—different too in New York, where Rockefeller, who commissioned the first version of this mural, destroyed it for its unsuitable political message.) Perhaps Varo’s birds are the same ones released by BenjamÃn Torres in his installation GuÃa de Campo (2008), which excises every illustration from a book of bird identification and sets them free across the green walls of the gallery.

In the next room to the bookshop, a dark negative which might be responsible for sucking the real thing’s energy away, is installed Marianna Dellekamp’s Biblioteca de la Tierra, a collection of book-sized vitrines filled with earth, sand, gravel and pieces of wood whose origins—Oaxaca, Paris, Saudi Arabia—are engraved on their spines.

I find myself, finally, back at Travazares, the bar beneath the Atrio on Orizaba, around the corner from Plaza Luis Cabrera. It was this neighbourhood that formed the background to William Burroughs’ sojourn in Mexico City in the early 1950s; where he began Queer, the novel which developed the style of ‘routines’ characterising the more celebrated Naked Lunch; and where he shot his wife, Joan Vollmer, during a disastrous game of William Tell, necessitating his flight from the country and casting a shadow over the rest of his life and his artistic output.

Burroughs liked Mexico City for its quack doctors who had few qualms about prescribing him the opiates he required to write—to function. Even if such purchases required long trips across the city, their undertaking could not be questioned: for all the distraction and the damage wrought, they are both fuel for and subject of his work, the backdrop to everything in which he engaged. Dragging myself, footsore, from bookshop to bookshop in a succession of unfamiliar cities feels much the same.

[…] made a side trip to Mexico City following his appearance at the SXSW conference in Texas. He blogged this week about his time there visiting the bookstores, including Péndulo, Atrio, LibrerÃa Pegaso, and MUCA […]

Pingback by James Bridle Explores the Bookshops of Mexico City — March 26, 2010 @ 6:19 pm

[…] The bookshops of México City. Fuente: Booktwo.org […]

Pingback by La semana en enlaces (26-03-2010) « el itacate — March 26, 2010 @ 6:36 pm

[…] James Bridle on a walking tour of the bookshops of Mexico […]

Pingback by Friday finds « STEVENHARTSITE — April 2, 2010 @ 10:33 pm