Today is International Migrants Day. Last week, I wrote about the failed deportation of Isa Muaza. Yesterday, Unity Centre Glasgow announced that another appeal by Muaza’s legal team had failed, and he was rescheduled for deportation, alongside a large number of others, on Tuesday night.

I heard at about 7pm that several detainees had been loaded onto vans at Harmondsworth Detention Centre and were on the move. I didn’t know where they were headed, but I knew that many previous flights had left from the private aviation area at Stansted Airport, a largely un-signposted collection of car parks and hangars on the western side of the airport. I arrived there at 8, just in time to see the first of several coaches and security vans, together with a police escort, arrive at the Inflite Jet Centre, a private customs and handling facility mostly used by private jets.

The coaches, five in all and probably from several different detention centres, arrived between 8 and 9, and were accompanied by silver vans bearing the logo of security company Tascor, formerly Reliance, who took over the role of deportation escorts from G4S in 2011 following the death of Jimmy Mubenga. Tascor has a page on its website called Our Values, where it boasts: “We steer clear of politics”. Most of the coaches were from WH Tours in Crawley, although one bore the bright yellow sun and jaunty typography of Just Go!

It is profoundly uncomfortable watching anonymous people of colour being loaded on and off vans and planes in the middle of the night under tight security. When you know a little of the background of the detainees, when you read their claims of torture and violence, their long battles to secure asylum, the institutional racism and homophobia, it’s terrible. But even without knowing these things, the manner in which it is done should tell you everything you need to know. The British Human Rights lawyer Gareth Peirce writes in Dispatches from the Dark Side, on UK complicity in torture, that “what is in fact the law precisely mirrors instinctive moral revulsion” but that “in this country, the government hardly needs such acceptance, since here the additional and crucial factor is that the public is unlikely to be given sufficient information to trigger revulsion.” Hence the night, the private terminals, charter flights, the hired coaches. All of this is deliberate: it is a policy of not being seen.

The detainees were kept on the coaches for some time, and there appeared to be some confusion about when they were going to depart. It’s standard practice in this situation to bring extra “reserve” deportees to the airport without warning, a practice condemned as inhumane by some MPs and the Inspector of Prisons. Before deportation, each detainee is issued with a plane ticket which gives the flight time – 22:20hrs in this case – and a flight number. As the flights are chartered, the flight number – here PVT091 – is internal, so it’s impossible to find out more details about it, except by going to the airport. The Home Office has been running deportation charter flights for some time, under as much secrecy as they can get away with, and refuses to disclose the companies involved in case it damages their commercial relationships. The ongoing deportation of Nigerians on charter flights is called “Operation Majestic”, but there are regular flights to many other countries, including “popular destinations” such as Pakistan and Afghanistan. Corporate Watch published a comprehensive report on what they call collective expulsion last month.

On the tarmac by the jet centre sat a Titan Airways 767. Titan Airways is based at Stansted, and describes itself as “the UK’s most prestigious charter airline.” Its fleet ranges from small business aircraft to widebodied airliners:

Since it’s foundation in 1988, Titan Airways has grown into the UK’s most prestigious charter airline, specialising in bespoke air charter, tour operator programmes and high end / corporate air travel as well as airline sub charter and aircraft leasing. It brings the very best standards of care and comfort to all its passengers. Once safely aboard, they can relax and enjoy our superb in-flight service and a wide choice of cuisine and fine wines to complete the experience. Titan’s modern, reliable aircraft can operate from all major international and regional airports day and night, 365 days a year.

It’s cold, and wet, and dark, and some of the deportees have been sitting on board coaches for hours, while Tascor guards mill about, smoke and chat. As it approached midnight, there was more activity around the plane, and it appeared that all the deportees were on board as the coaches left the terminal compound empty and parked up outside. (The next day, Unity tells me that two people were taken off the flight at the last minute, but those people estimated that around 80 Nigerians and Ghanaians were on board, including Isa Muaza, who was taken straight to hospital on arrival in Lagos, and a woman who married a British citizen two years ago, and was not expected to be deported).

You can watch flights taking off from the far side of the airport, from a muddy lane alongside the north end of the runway. On the way over to it, I was stopped by the Police, who had been told I had been seen around the private aviation area. They were happy that I was a ‘spotter’ looking for planes – and advised me to join Essex Police’s Plane Watch scheme – but also warned me that the private aviation section was a restricted area, and I shouldn’t go there.

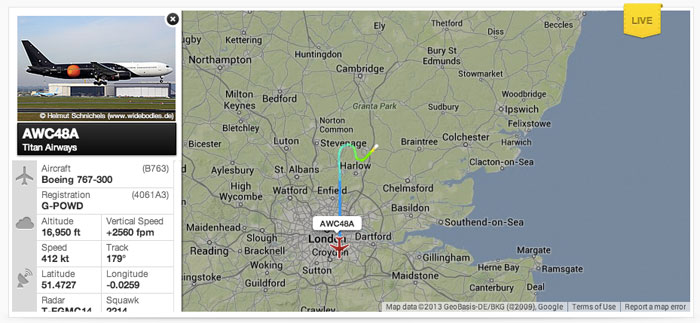

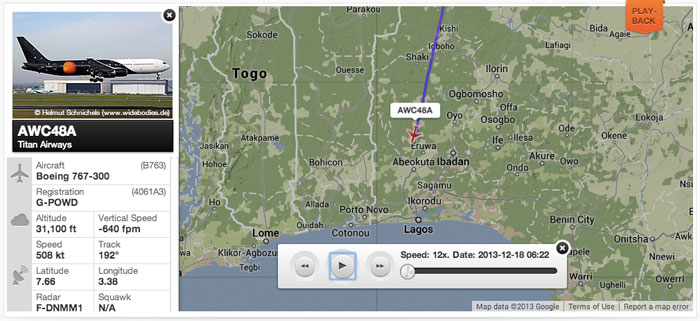

At 00:27, the Titan Airways 767 roared down the Stansted runway and into the night. Moments before, its call-sign appeared on Flightradar: AWC48A. And from there, an aircraft registration number: G-POWD.

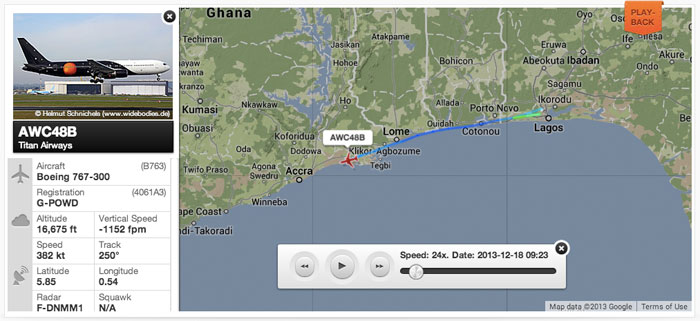

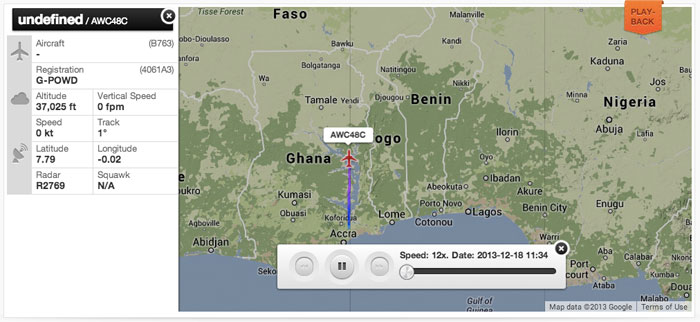

We can see G-POWD on approach to Lagos a little after 6am. Two hours later, it’s on the move again, making the hop westwards from Lagos to Accra, the capital of Ghana, where it makes another stop. And then at 11am it appears to lift off back in the direction of London – at time of writing, it is probably somewhere over North Africa.

When I got back to my car around 1am, I had a flat battery, and had to wait for a repair man. When he arrived, and I explained what I was doing in this godforsaken place, he told me he’d been at the Inflite Terminal recently too, to jump-start a brand-new Tascor transporter van, whose driver told him these flights happen all the time, and nobody knows about it, not even most of the people who work at the airport. “Makes you think,” he said. “Makes you think.”

*

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.