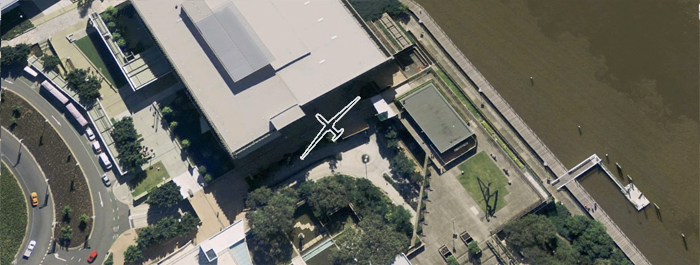

This week I was due to install another Drone Shadow, this one in Brisbane, Australia (that’s a planning mock-up, above). I had been invited by the Brisbane Writers Festival, and we had received permission from the Queensland State Library to install the work on their premises. Unfortunately, due to the actions of Arts Queensland, the department of the State Government with overall responsibility for the arts, it has been impossible to proceed with the work. The actions of Arts Queensland in this case have been both incredibly frustrating and boringly familiar: they have stalled, dissembled, obfuscated and lied, all in the service of silencing an artistic work and preventing a proper debate occurring, either about the work, or the government’s censorship of it. (For the record, there is a full account of my dealings with Arts Queensland available here.)

I’ve often been asked if I have got into any kind of trouble for creating the Drone Shadows before, and the answer has always been no. This is despite the fact that we have drawn them in Istanbul, during a period when the Turkish government was in negotiation to purchase Predator drones from the US, and in Washington DC – right next to the White House – at the height of the US drone war. But apparently the image – the bare outline – of a drone was too much for the government of Queensland.

In Istanbul we drew a Predator, in DC a Reaper. In Brisbane I proposed to draw a Global Hawk, the largest military unmanned aircraft currently in service. Late last year it was revealed that the United States flew secret Global Hawk spy missions from Air Force bases in Australia in 2001-2006. The programme was revealed by a group of amateur aviation historians who tracked the Global Hawks arriving and taking off. When they revealed details of the flights, they were visited by Australian defence security officials who demanded they not reveal details of the flights. An Australian senator who proposed to notify the public of the flights was silenced by the US Air Force, which demanded the flights remain classified.

Since then, Australia has been in prolonged negotiations with the US to purchase Global Hawks itself, announcing an AU$1 billion programme in 2004, rising to AU$3 billion in 2012. The latest election, which takes place quite coincidentally this Saturday, has led to further fierce debates over Australian defence and the drone program.

Australia’s domestic drone program is primarily aimed at “securing borders”, and its preference for maritime versions of the Global Hawk is due to the need for surveillance of immigration by sea. This program aims to ensure, in the words of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd in July 2013, that “any asylum seeker who arrives in Australia by boat will have no chance of being settled in Australia as refugees”, by shifting the problem to neighbouring countries such as Papua New Guinea. There is also a long history of asylum claimants being housed at former Air Force bases – and a long history of government objection to artworks dealing with the subject: see for example the story of Escape from Woomera, a political computer game about a detention camp in a remote Australian Defence Force base in South Australia.

One of the many reasons given by Arts Queensland for their opposition to the installation of the Drone Shadow was the opening at the Queensland Museum next door of an exhibition of thousands-year-old artefacts from Afghanistan, to which members of the local Afghan community had been invited. Arts Queensland expressed their view (after several weeks of denying any such issue) that this community might be made uncomfortable by the work. The community was never consulted, and the Museum itself raised no objection. Arts Queensland called it a “raw issue”. Indeed it is.

Australia’s Defence Forces have been involved in the war in Afghanistan since 2001. This contribution has included ships, manned aircraft, ground troops – and, more recently, drones.

The Royal Australian Air Force has been using drones in Afghanistan since 2009, when it first started to deploy the Israeli-built Heron drone, a twin-hulled surveillance drone the size of a light aircraft. At a 2012 promotional event on Australia’s Gold Coast, a short drive from Brisbane, Australia’s most senior military drone commander stated that the drone program was “like crack cocaine, a drug, for our guys involved – [they] just can’t get enough of it.”

These drones are in fact still owned by the Israeli manufacturer, and leased via a Canadian company – as Australia’s ABC News put it: “Israeli-owned drones, leased by Canadians, flown by Australians, fighting a war against Islamist insurgents in Afghanistan”. The RAAF drone teams are trained by Canadian and Israeli civilians at Amberley in Queensland, on the outskirts of Brisbane. Before they deploy to the field, they spend hours test-flying the drones over a simulated Afghan village, constructed in 2011, on the Woomera test range, close by the notorious refugee detention centre. (Picture above: a Heron drone parked at Woomera Air Base, South Australia, via Google Earth.)

The RAAF’s Herons are nominally unarmed, but they are equipped with lasers which allow them to mark targets for incoming airstrikes or artillery – the networking of contemporary military forces means that the formal distinctions between the capabilities of different weapons systems are increasingly meaningless. The drones are a key part of the “kill chain”, the process by which targets are selected and attacked by the entire system, and the ADF also calls on US and British armed Reaper drones to support its ground troops in battle.

In describing the contours of Australia’s relationship with drones, we see how, once again, such relationships extend beyond the individual aircraft to encompass far wider issues including domestic politics, international relations, warfare, immigration and networked technologies.

Drones are avatars of the the political process: they are instantiations of a set of ideologies and beliefs, made visible by their reification in electromechanical systems. When we talk about drones, we are really talking about the politics that demand, shape, and deploy them, and the politics which are made possible by them. This politics reflects the drones themselves: it is a politics of violence, of obfuscation, of radical inequality of sight and action, and it is sustained by that obfuscation and that inequality.

No wonder then that politicians are afraid of even artistic representations of the drone. No wonder they cite feelings of “discomfort” at even mentioning them, although in projecting this discomfort onto an immigrant population – without consultation – they reveal even more clearly the complicity of the technology in war and social oppression.

The Drone Shadow is not just a picture of a drone. It is a diagram of a political system. Every time we draw one, we use it to cast light on the actors who would prefer that the reality of their intentions and actions remain hidden.

This is the nature of networked technology today: it is the product of an embedded politics which it simultaneously obscures, through its apparent sophistication, and renders startlingly visible, through its explicit form. That invisibility is the intention of power; rendering it visible is the intention of art.

In the present case, power in all its petty exercise has done its utmost to render such a debate invisible. That it has succeeded for the moment, with the barest minimum of opposition from the cultural institutions which should oppose such exercises at every step, is saddening. It is also, I have to believe, unlikely and impossible to remain the case for long.

*

If you would like to draw your own Global Hawk shadow, you can download a schematic for the installation here.

Comments are closed. Feel free to email if you have something to say, or leave a trackback from your own site.